lo-fi nostalgiacore braindump

Liz Pelly, Mood Machine (2025)

One of my semi-regular complaints about getting old is that I’m just not able to read with the same degree of speed and retention than I was ten, twenty, or thirty years ago. The speed stuff is easy enough to understand, considering that I’m coming up on the one-year anniversary of cataract surgery in both my eyes. My physical capacity for reading has bounced back somewhat, but I still get visually tired more easily, use eyedrops, etc.

The mental side of things feels like it’s more permanent. No matter how snugly I’ve managed to tuck in books and ideas in my youth, my brain gets fuller, and adding new information feels like I’m approaching the upper range of the Tetris board, and struggling to complete a row. I know that the sci-fi metaphor of jettisoning early memories in order to make room for new ones is flawed, but it feels true to me as I struggle to remember names, specialized vocabulary, and the like, all in service of keeping up with the Discourse, and making steady progress on my book manuscript.

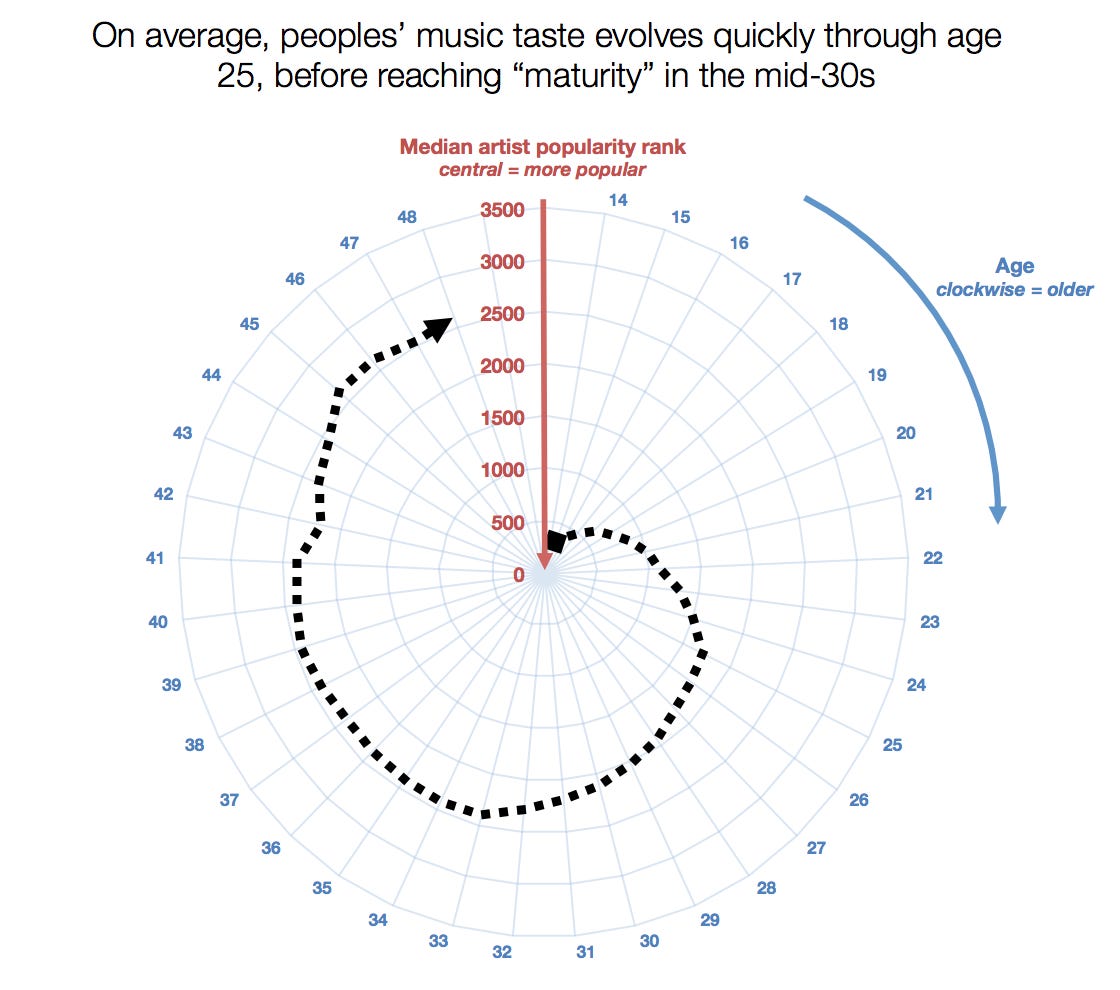

About ten years ago, when I was deeper into digital humanities and thinking about how to talk about and work with what was once called big data, I came across a really interesting illustration of those things1. It’s a study that makes use of the data that Spotify was gathering at the time, and articulates an idea that sounds really obvious, but is tricky to actually prove.

This graph comes from a post by Ajay Kalia, called “Music was better back then”: When do we stop keeping up with popular music? There’s more to the study than the information represented above, but this was the bit that interested me most (and I thought the “graph” was pretty clever as well). It demonstrates what Kalia describes as a “coolness spiral of death,” whereby teenagers are streaming (and presumably driving) the most popular music at the moment2 while older consumers are sliding down towards the long tail of artists3. They’re less likely to “replace” the music of their teens and twenties with whatever’s current.

There are all sorts of implications to this data that get at our cultural, collective relationship to music. My own personal experience moving along this graph matches up with my own listening habits—I’ve aged off the graph entirely (!!) and I’m far more likely to build a playlist around the music from my high school and college years4 than I am to find out what’s current. But this isn’t entirely a direct function of age. One piece of it is that music occupies a different (smaller) role in my life as a fully grown adult than it did when I was willing to spend disposable income on records, tapes, CDs, concerts, and the like. And of course, technology is an even bigger part of that—there are no record stores to visit, radio feels far more corporate than it used to, and MTV was a much different place for my generation.

In fact, I’d go so far as to say that the graph above, because it was generated on 2015 data, in the earliest stages of Spotify’s near-monopoly on music, actually reflects a pattern based on a model of music consumption that has largely vanished in the process. It would have been impossible to gather enough data to produce that graph prior to the 2010s. It’s not that people weren’t listening to music; rather, the media through which they did so were significantly more dispersed and diverse. As Spotify began to take over that distribution, my guess is that listening habits on the platform probably echoed listening habits formed in the era of record sales and radio airplay. At some point, though, I’m certain that this relationship inverted. Did it invert to the point that Spotify users started being molded to the platform in such a way that this maturation pattern locked in? (It would have been child’s play to algorithmically force feed younger users more popular and current music, with looser recommendation metrics for older ones.) I don’t know, and I don’t think that Spotify would ever release the data that could test this hypothesis.

But think of it this way: when my generation was growing up, “staying current” meant visiting those stores, spending time with radio and/or MTV, etc., the friction-bearing activities that made currency something to accomplish. Those of us who cultivated niche awareness worked even harder at it—I wore out the “Imports” bin at my local record store to find British post-punk albums to add to my collection. For the better part of the past decade, though, we can just open the app and select whatever clever name Spotify has assigned to contemporary, blockbuster, music industry fare. They can lock us in at the center of the graph, effortlessly.

As I revisited this essay, I thought that it would be kind of cool to have these spiral graphs for each year (in the way that Kalia provides different options based on gender, parental status, et al.). It’d be interesting to see how the y-axis (the red diameter of Kalia’s graph) changes and slides over time. So I did hop down the rabbit hole of looking up Spotify’s “top” artists, only to learn that 5 or 6 of the top 10 from 2015 are still among the top 10 in 2024 (most of the rest hadn’t begun releasing music 10 years ago). If indeed we were to replicate Kalia’s data across the past ten years of Spotify’s consolidation of the industry, my guess is that there’d still be enough listeners of an advanced age (old like me) to preserve some of the coolness spiral. But I wonder if the center of the graph (what would be the early part of the x-axis if it were uncurled) is compressing in favor of the megapopular artists.

There are a few different ways to interpret this. One is to say that folks’ taste is “maturing” earlier and locking in place, I suppose. Another way is to ask whether innovation has slowed down across the industry—maybe there are no longer as many new artists or sounds to replace the old ones. Both of these things are possible—the idea of cultural stagnation in particular is something that Ted Gioia has speculated about recently5.

The third perspective on this phenomenon is a bit trickier to unpack, because it sees this stagnation (across cultural milieux) as an intentional byproduct of digital platforms. Jaime Brooks, who also features in The Atlantic piece above, describes these platforms’ effects with a single word, “wreckage.”

Streaming encourages artists to play an enervating game of scale: The more songs they release, the more chance they have of going viral and turning pittances into real income. Artists are thus motivated to record as quickly and cheaply as possible. All of this, Brooks believes, has led to a glut of music—both popular and obscure—that is plainly bad: less distinct, less soulful, and less skillfully made than the minimal standards of previous eras. “Nobody can get the resources to develop their craft,” she said.

It’s worth noting that Spencer Kornhaber, who interviewed Gioia, Brooks, and others, and frames the piece, is himself optimistic despite the critiques he shares. But I want to turn to one more source, the book that was originally the impetus for my trip down this rabbit hole, and that’s Liz Pelly’s recent book Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist.

Leveling the playing field

First things first, Pelly’s book is outstanding, so much so that I’m not going to be able to treat it in nearly as much detail as the book itself provides (or deserves). You’ll recall that I cited an online excerpt from the book as I wrote about the way that social media platforms are using Ai to generate slop content as a means of crowding out humans (and thus capturing more attention and revenue for themselves). That excerpt is incredibly dense with information and perspective. At the time, I wondered if it had been condensed, the way movie trailers tend to condense narrative to give you a larger sense of the plot. Having read the full book now, I can assure you that this is not the case—the entire book maintains the same levels of detail, examination, and judgment6. This book exemplifies longform journalism, in a way that is distinct from both academic non-fiction and access journalism.

This is how I would break it down for you: Perhaps more than any other essay or book I’ve read, Mood Machine traces out what I’d call the enshittification playbook. Looking at a single platform (Spotify), it closely examines the actions and behaviors of its ownership over its lifespan, and it provides a clear-eyed accounting of the impact that those decisions have had on the array of stakeholders involved. It tells an important and non-obvious story about the way that music (as both industry and culture) has changed in the past decade or so, becoming a site of extraction that sacrifices sustainability, variety, and human flourishing on the altar of corporate profit.

If you read me regularly, you’ll know that one of my least favorite coinages in all the world is the idea that the internet “puts the world at our fingertips.” This is one of the foundational myths of the internet, designed (and repeated ad nauseam) to distract us from the fact that it’s actually put us at the world’s fingertips. Thanks to Pelly, I’m now adding another phrase to my personal devil’s dictionary7: “leveling the playing field.”

Pelly notes early on in Mood Machine how fond Spotify was of this phrase as a way of characterizing its intentions and impact: “All of this so-called innovation was going to “level the playing field” for artists, Spotify obsessively promised” (viii). The idea of a level playing field for participants/competitors has long been a (sports-based) metaphor for equity—it signifies equal opportunity, a fundamental fairness in terms of the conditions and rules under which we operate. It doesn’t mean that there won’t be winners and losers, but that external factors don’t privilege one player or team over another. As Pelly explains, Spotify wasn’t exactly walking the walk:

Spotify obsessively talked about how it was leveling the playing field, but there were plenty of anecdotes suggesting otherwise. Certainly something was being leveled—flattened, smoothed out, homogenized. Beneath leveling the playing field is a deeper assumption, too, that artists should want to be operating in a one-size-fits-all model—or that independent artists should want to conform to the norms of the winner-take-all pop star system (34).

I’d take her analysis one step further. Spotify is in the process of leveling the playing field, not by making it level for everyone, but in the sense that we talk about leveling a building—destroying it.

Spotify’s not the only culprit here. Music was already being dematerialized and distributed over the internet in the Napster/Limewire days, and the oligopolies in charge of music (and movies) responded by inciting panic over piracy. In many ways, their long term solution was to build a deeper, black-boxed piracy ecosystem, one that relied on what I’ve described as hostagery, the same dynamic that governs our streaming channels, Kindles, and an increasing number of our physical goods8. We license our possessions, and pay unending fees to maintain access to them. In this way, Spotify is just another rentier in an economy that is rife with them.

As Pelly makes clear in her book, though, Spotify has been particularly effective in adapting this strategy to the music industry. Here’s where I’ll struggle to do justice to the level of depth and detail in Mood Machine, but I’ll try to summarize a bit. The site has gradually shifted its emphasis from accessing individual artists to “playlists,” and those playlists are constructed around moods, activities, identities. Pelly describes this as a “cultural devaluation” that’s accompanied the financial impact that the site has had. “If the streaming economy has contributed to any major cultural shift in recent history, it might be that it has helped champion this dynamic of passivity.” Choosing a playlist gives over control to the site itself, under the same guise (“algorithms are democratic!”) that other social media have used to cloak their own manipulations.

By design, it’s a system that distances users from the people and communities that create, record, and distribute music. Spotify’s own research confirmed for them that their consumers were just looking for background noise. As one former Spotify employee explains, “The vast majority of music listeners, they’re not really interested in listening to music per se. They just need a soundtrack to a moment in their day.” According to this employee, Spotify’s CEO bragged that “Our only competitor is silence.”

Their business model has retreated further and further from connecting artists to listeners. While there’s a long history behind mixtapes and playlists, Spotify has followed a long arc towards Muzak. First, they shifted their emphasis towards playlists, then they eliminated the employees who were curating those lists, preferring instead to build them around cheaply produced stock music (while charging artists a higher percentage of their royalties to gain privileged access to playlist appearances). And now that stock music, once generated by Spotify-owned “production” companies, is being produced by AI, even as they manufacture fake artist profiles to hide the fact. (Not unlike a once-venerated sports publication.) As Pelly asks, partway through the book, “Fake mood music streamed by fake listeners: Is that where the arc of recorded music industry ‘innovation’ eventually leads? (125)” She’s commenting here on the “stream farms” that the industry employs to goose their artists’ streaming numbers, but we ourselves are predominantly “fake” if we’re paying a monthly fee for the privilege of background noise.

There’s more to the story, from the multi-level payola scams that Spotify runs at every level to the massive data collection that they engage in (and the various corporations they sell that data to). What was offered to us as a “democratization” of a deeply exploitative industry on the one hand and a way to repair the damage allegedly caused by piracy on the other has managed to lock in the worst parts of both, all while they mask this activity in some of the most persistently optimistic smoke and mirrors to be found among social media platforms. Mood Machine traces out this massive network of decisions and does a great job of including the voices of those who have been shut out.

Pelly is not entirely pessimistic. She closes the book with some of the ways that arts labor has organized in Europe, and that local communities (and libraries) have worked to revitalize their communities, for example. But there’s no single answer, she explains, and finding that range requires us to think not in terms of the individual consumer but “diverse cultural ecosystems.”

When we think about repairing the broken world of music, we need to think bigger than just fixing the music industry. The way music has been reimagined by streaming is grim—but these problems are ultimately manifestations of a music industry that has been failing artists and the public for generations. To address the root causes of our ailing music culture, we need to have deeper conversations about why music matters, why universal access to music matters, and what systemic political and economic realities currently prevent so many people from engaging deeply with music.

Mood Machine is a great place to start. It took me longer to read than I’d planned, but I’m glad I stuck it out, and recommend it to you. If nothing else, it’ll help you reconsider your monthly Spotify subscription. More soon.

I should point out here that retrieving this essay would have been impossible had I not been using Instapaper at the time. Services like this allow to age a little more gracefully—they add more rows to the Tetris board, as it were.

This data is from 2015, and the #1 artist was Taylor Swift

I just saw a piece at The Onion that satirizes this idea, the differences in taste between teenagers and their “cool” parents.

If you want that playlist, check out one of my very first Substack posts, and scroll to the bottom. I’d still listen to that mixtape.

This recent interview with Gioia in The Atlantic provides a fair account of this position, by someone who doesn’t quite agree with him. The whole piece is worth reading.

As a consequence, the book reads more slowly than most of the general audience non-fiction that I read. It took me longer to read because there was just so much of it.

I don’t have a formal name for this. I thought about “malexicon” as a portmanteau of mal- (evil) and lexicon, but that feels like it needs its own post. So for the moment, I’ll settle on referencing Ambrose Bierce’s classic.

See Aaron Perzanowski & David Schultz, The End of Ownership: Personal Property in the Digital Economy for more on this…

People don't use the term "Big Data" anymore? I know it had its heyday re: computation turn, but people still use the term right?