One thing that happens to my writing from time to time is that I’ll be writing through an idea or a thought that I’ve had, and in the process, I’ll toss out a secondary idea that ends up sticking with me. This happened several times in my book, where the passages that ended up being important to others were things that just got me from point A to point B. It’s a weird feeling. On the one hand, it allows doubt to sink in—maybe the things that I think are important aren’t actually? On the other, I really think that’s how language works. Our thoughts vibrate with frequencies that aren’t entirely under our command, and we never have as much control over language as we think we do. I find that cause for celebration, honestly.

Anyways, I tossed up a line on Tuesday that I’ve been thinking more about:

It’s the legal version of ransomware: someone comes up with a good idea, lots of people rush to embrace it, then whoever’s in charge takes their enthusiasm as a sign to turn their priority to profit…

The idea that enshittification makes use of the same structure as a ransomware attack is something that really only just occurred to me in the moment of writing, and yet…

Ransomware is one of those things that most of us don’t worry much about. But it was a plot point in a novel that I read this summer, and I’ve seen it a few times now similarly deployed in tv shows and movies. While it’s allegedly declining in effectiveness, it still costs businesses and organizations hundreds of millions of dollars a year (to say nothing of the destruction it can wreak on smaller institutions). The basic structure is simple: a ransomware attack is an assault on a network that locks out its users and either threatens to release the data or permanently block access unless a ransom is paid.

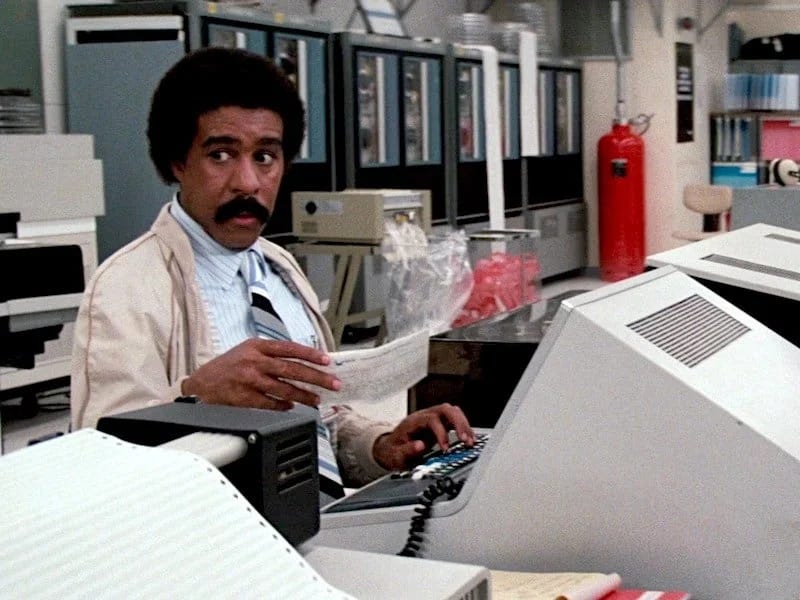

As we’ve come to rely more and more upon personal devices and upon networks for the day-to-day operation of businesses and organizations, it makes sense that ransomware would become the threat it has. When I was growing up, the commonsense view of hackers was that they were folks were skilled at gaining access to systems, where they could steal sensitive information, make changes, etc. Think of Richard Pryor in Superman III diverting fractions of pennies from millions of transactions to make himself rich.

It was surely more complicated than this, but we were encouraged to think of hackers as akin to thieves, illegally penetrating digital strongholds and making off with something valuable. Ransomware operates by a different model—the point isn’t to access valuable information per se. Instead, its aim is to seal off the network and to make it unusable. For the vast majority of folks, having one’s medical records stolen/duplicated wouldn’t be the end of the world, but if all of a sudden, none of your health professionals had access to them, over an extended period of time, the results could be catastrophic.

As the title of this post suggests, I’ve been thinking about this in terms of taking or holding us hostage. In the case of a ransomware attack, it’s a pretty obvious metaphor, to the point of naturalization. But the more I’ve thought about it, the more I began to realize just how many of the things in my life are essentially hostage to someone/something else.

It took me a long time to truly buy in to the Kindle app on my iPad. I still purchase more than my fair share of paper books, but increasingly, as my eyesight continues to deteriorate, my Kindle library has grown. It’s just easier for me to read on a backlit screen where I can tweak the font size. And obviously, I’ve paid for the books in that library. But honestly, what’s to stop Amazon from deciding at some point in the future that I should be paying them a fee every year to retain access to those books?

You should be able to see where this is going. I haven’t used a CD player to listen to music in decades, or a DVD player to watch movies in nearly as long. I don’t “own” those things, even though I’ve paid for them. They are instead hostage to the distribution channels through which I access them, an access that I pay for monthly, but ultimately have no control over. If I stop paying the fees, I’ll have nothing but memories to show for it. The same is true of much of the software that I use, and increasingly, the vehicles we drive, the appliances we live with, and the institutions we rely upon are all dependent on the uninterrupted “goodwill” of a small handful of corporate overlords. We’ve even all but lost the right to repair the things we do buy.

We’re not encouraged to think this way, to consider how much our lives are held hostage. But it’s a core tenet of contemporary market capitalism, where despite the continued popularity of arguments regarding “free markets,” the fact is that most are anything but free. We’ve seen this most starkly in the tech industry, I think, but the goal for most corporations nowadays isn’t to enter a particular market and win it, but rather to create a market and then prevent anyone else from joining it for as long as possible, with the end goal of establishing a monopoly. In the case of established markets, there are alternative paths to “victory”—one might use the economy of scale to drive our competitors, exploit lax anti-trust protections through vertical mergers, lean on the culture to naturalize proprietary eponyms (Xerox, Kleenex, Google, Uber), etc. Perhaps the common feature across these various markets is that, once they near monopolization, what few companies are left compete not with each other, but with us—and they work the system to protect their advantage, of course.

We’re surrounded by consequences: the glasses that I bought last year to compensate for my declining eyesight? They cost maybe $15 to manufacture, while I paid hundreds of dollars for them, thanks to the stranglehold Luxxotica has on the US eyewear market (estimated to be worth about $150 billion).

But honestly, I was thinking about this in a couple of different contexts. A few weeks ago, as I was talking to my department about AI, I mentioned that genAI writing tools are in the “charm offensive” phase of their development, where their goal is to capture market share, price out competitors, and dazzle us with all of the AmAZiNg things that they can do. Once folks have bought in, it’s only then that the hostage phase begins, where our embrace and reliance upon these tools is translated in turning profits. I was thinking the other day about how many people I know (myself included) have yet to fully abandon Twitter, and their reasoning all sounds remarkably similar. We’ve imbued that platform with so much implicit value in terms of contacts, networks, reputation, etc., that those things are now hostage to X.

I’ve been thinking too about how this functions rhetorically, how certain (bad) actors will take phrases hostage. It’s happened over the past couple of years with critical race theory, a school of thought that has nothing to do with the bullshit that’s been mounted in opposition to it. And I’m watching the same now with the idea of “parents’ rights,” which, as far as I can tell, is little more than a doublespeak euphemism for a pretty regressive ideology. As Jamelle Bouie notes, “The reality of the “parents’ rights” movement is that it is meant to empower a conservative and reactionary minority of parents to dictate education and curriculums to the rest of the community. It is, in essence, an institutionalization of the heckler’s veto…” I wish I could say that this is a step away from criminalizing disagreement, but that moment has already passed in multiple states, including the state where I was born and raised, whose public education used to be among the best in the nation. Rather than relying on our leaders to negotiate our release from our captors, we’ve seen them now become the thought police that 1984 warned us of.

I don’t have any particular conclusion here, nor really any sense of how we might reverse things. But I’ve become a lot more conscious of how captive our economy has become, a development that has been encouraged by leaders across the political spectrum. (I’m fairly sure that I’d argue that our politics are being held hostage by the idea of left-right spectrum, polarized or no.)

This is a very linky post, moreso than normal for me. And I’m sweeping through a lot of ideas, but I wanted to get them all situated. Cory Doctorow’s new book is out this week, and I expect there’ll be some overlaps, so I wanted to lay this down before I turned to reading it. More soon. -cgb