Escape to Canny Valley

Degenerative Ai

10 years ago this month, I attended the first ever Affect Theory Conference in Millersville, PA. My talk was called “When Algorithms Attack! The Affective Consequences of Social Media1.” In large part, it was about the studies that FB was conducting (without consent) on how to manipulate their algorithm to increase engagement, how to addict us to its service. Or to put it in terms I used in my last episode, they were figuring out how to draw us into their web and keep us there as long as possible. I guess you could say I’ve been thinking about these ideas for a while now.

I was thinking about that conference presentation this week in part because one of the people I cite in it, and who gave one of the many amazing plenary talks at the conference, was Natasha Dow Schüll. Her book, Addiction by Design, was formative, not only for my talk, but for my attitude and intellectual approach to social media going forward. But I’m going to come back to Schüll in a bit.

Chatbots & Cultural Dopes

Last episode, I talked about how the same properties of language that writers use to immerse us in narratives (novels, movies, shows, et al.) are being deployed by Ai developers in an attempt to ensnare/enclose us in that particular hall of mirrors. But there’s an important caveat that I didn’t get into.

When we read a novel or watch a movie, it’s a relatively simple matter to decide whether we belong in that fiction’s implied audience. Unless the fit is particularly jarring, we aren’t even making that decision consciously; I’m assuming that most of us aren’t bibliomercenaries, stopping after Chapter 1 to make an overt decision whether or not to keep reading. And yet, it’s easy enough to set a book aside, because we’re making the choice in the first place to take it up.

Agency is one place where the analogy between chatbots and fiction breaks down a bit. We are bombarded on the regular by commentary, advertisements, and vibes telling us that our entire world will be overrun by artificial intelligence any minute now. But more to the point, Ai chatbots are relentlessly adaptive and committed to the illusion of the implied author. No one who reads If on a winter’s night a traveler believes that Italo Calvino is talking specifically to them, but Claude and Gemini will address you by name, adapt to your language and interests, and do everything in their power to behave as though there is someone, albeit digital, on the other side of the screen, someone who can seem very invested in your satisfaction (and engagement).

We’ve seen a lot of press over the past six months given over to “Ai psychosis,” the umbrella term for situations where “AI chatbots may inadvertently be reinforcing and amplifying delusional and disorganized thinking.” To be a little unfair, this line from Psychology Today feels more “legally permissible” than accurate—the absence of safety and alignment guardrails in our chatbots is less a bug than a feature, as corporations race to capture market share. Coverage like this tends to frame it as a user problem—if they’re already delusional, after all, then we can hardly blame (unregulated) Ai, right2?

The quiet part of this framing is that this sort of thing could never happen to us—we’re too smart, savvy, or self-aware to allow ourselves to be taken in by these tactics. This entire package of attitudes was described by Howard Garfinkel (in the 60s) by the phrase “cultural dopes.” It’s a critique of the idea that scholars are able to pierce the veil of, say, advertising campaigns and cultural narratives, while “normies” are subject to their influence, “unreflective rule followers who reproduce patterns of action without being aware of how they do so3.” Because “psychosis” discussions tend to highlight the most extreme versions of this phenomenon, it’s easy for us to fall into the trap of imagining that there’s something wrong with the people rather than artificial intelligence itself, that they’re “dopes.”

Degenerative Ai

Another area where the idea of “dopes” can prevail is with discussions of gambling, and that’s part of what made me think about Schüll’s book, which maps out the entire ecosystem around “machine gambling.” She visits casinos, attends specialist conventions, and synthesizes a great deal of scholarship on gambling, but maybe most importantly, a significant chunk of her book draws on her interviews with gambling addicts themselves. These are people from many walks of life and backgrounds, united mainly by the fact that they have surrendered their lives to the highly engineered, designed, and promoted gambling industry. Unlike the handful of people who jet around the world to high-end poker tournaments, though, or those who appear (with increased frequency) as experts on NFL broadcasts4, these are people perched on stools in Vegas who empty their paychecks (and sometimes their entire lives) into video slots or poker, disconnecting from one world to enter another.

The stories that Schüll’s book offers, about the people who have lost themselves in this world, are genuinely heartbreaking. They are people whom we dismiss as “degenerates,” who lack the willpower to separate themselves from gambling. One of the overarching themes of the book, though, is the extent to which these corporations (casino owners, game developers, et al.) have endeavored to create something that Schüll describes throughout as “the zone:”

I ask Mollie to describe the machine zone. She looks out the window at the colorful movement of lights, her fingers playing on the tabletop between us. “It’s like being in the eye of a storm, is how I’d describe it. Your vision is clear on the machine in front of you but the whole world is spinning around you, and you can’t really hear anything. You aren’t really there—you’re with the machine and that’s all you’re with.”

Schüll is critical of the fact that “the preponderance of research tends to concentrate on gamblers’ motivations and psychiatric profiles rather than on the gambling formats in which they engaged.” And this despite the fact that, by the turn of the century, gambling addiction had shifted from traditional milieux (sports, dice, cards) to “machine gambling,” to the tune of 90+ percent by the year 2000. This is a qualitative shift that went largely unnoticed; while more traditional gambling might have been more economically motivated, Schüll explains that “it is not the chance of winning to which they become addicted; rather, what addicts them is the world-dissolving state of subjective suspension and affective calm they derive from machine play.”

Addiction by Design feels more relevant to me today than it did when I cited it in service of my presentation 10 years ago on the parallels it offers with social media. The turn towards surveillance, data extraction, hyper-tailored algorithms, all in the service of constructing platformed enclosures, puts me in mind of the tag line from In Formation magazine, “Every day, computers are making people easier to use.” As I wrote about a couple of months ago, Ai is taking all of the training that we’ve inadvertently provided through social media and using it both to ensloppify those platforms and to build its own, in the form of companion apps and chatbots.

One last thing that I want to pull from Addiction, though, is that idea of the “zone” that animates so much of Schüll’s discussion. If we’re not to think of these gamblers necessarily as degenerates, how instead should we consider them? According to Schüll, “what they seek is a zone of reliability, safety, and affective calm that removes them from the volatility they experience in their social, financial, and personal lives.” They’re not looking for a quick buck, and many of them are aware of the damage that they’re doing to their lives outside of their gaming. Schüll cites (secret syllabus stalwart) Kenneth Burke, who writes about converting chaos and loss into certainty, explaining that

Gambling addicts often spoke of their machine play as a way to convert accidental, unwilled loss into “willed” loss of the sort Burke points to, as when Lola remarked: “It’s me hurting myself and not something else [hurting me]; I’m the one controlling it.”

Even when their gambling was guaranteed to end in disaster, many of Schüll’s participants took solace from the fact that it was their decision; one interviewee wanted “a reliable mechanism for securing a zone of insulation from a ‘human world’ she experiences as capricious, discontinuous, and insecure. The continuity of machine gambling holds worldly contingencies in a kind of abeyance, granting her an otherwise elusive zone of certainty…”

The Canny Valley?

Rather than framing our nascent encounters with chatbots as a form of psychosis, one that can be dismissed as psychological weakness on the part of a small set of “bad apples,” it might instead be worth following Schüll’s lead and thinking about why so many people find themselves turning towards Ai, what these platforms are providing that appeals to them.

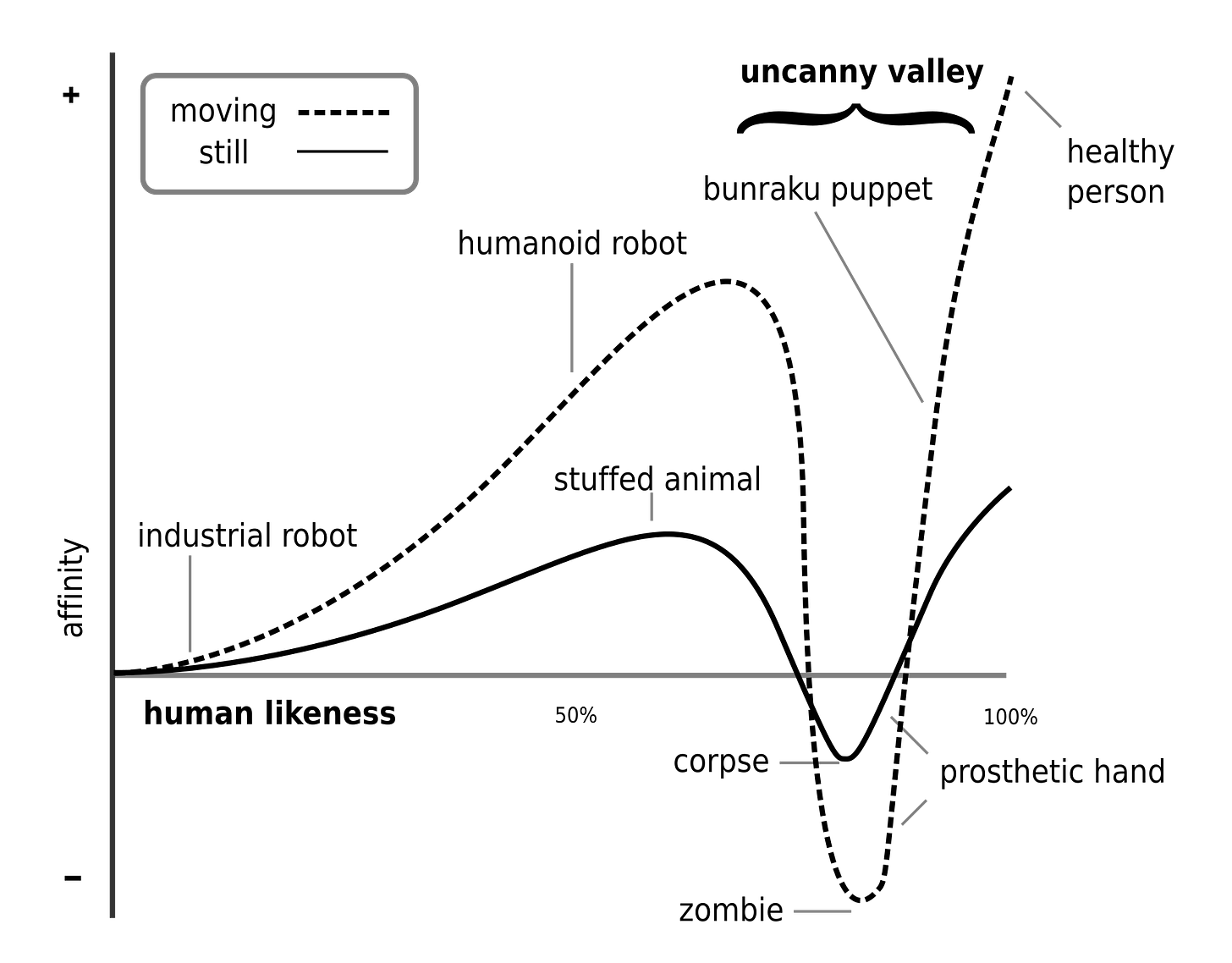

The “uncanny valley” is a hypothesis about our emotional reactions to near-natural representations. It holds that “an entity appearing almost human will risk eliciting eerie feelings in viewers.” (Personally, I react most viscerally to cgi-animated animals digitally manipulated to behave like humans.) But the hypothesis comes from robotics originally: “some observers’ emotional response to the robot becomes increasingly positive and empathetic, until [the robot] becomes almost human5, at which point the response quickly becomes strong revulsion.” The term itself comes from that dip in the graph above.

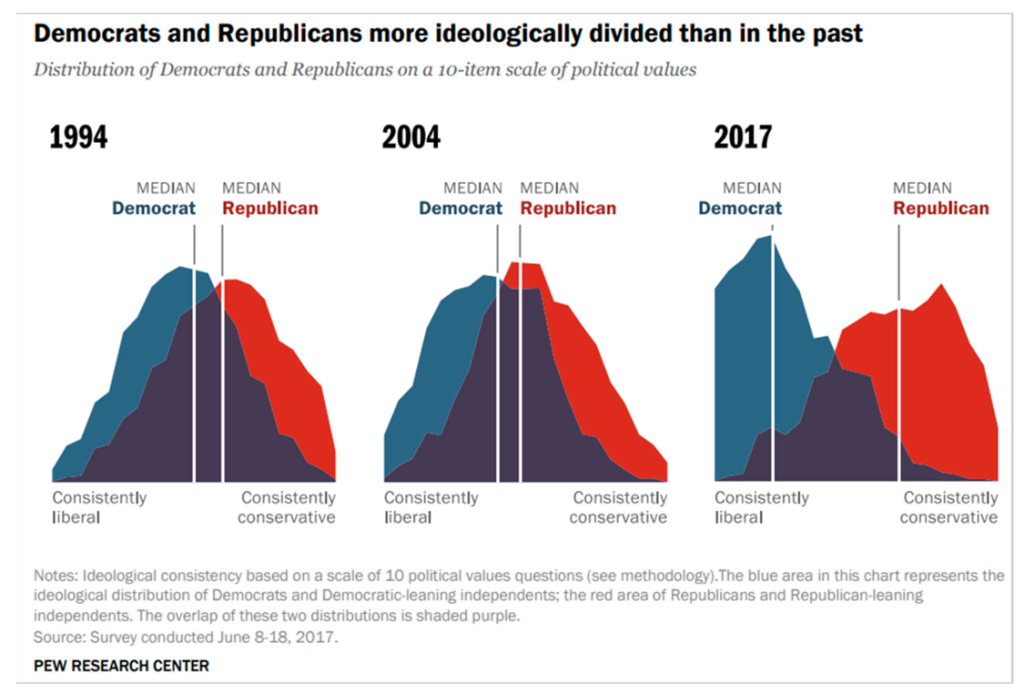

At a time when so many of us experience the world as increasingly “capricious, discontinuous, and insecure,” that zone of certainty that Schüll’s gamblers retreat to begins to sound more appealing. I want to take the idea of an uncanny valley and flip it on its head, by way of a couple of additional illustrations. The first is from a Pew report on political polarization in the US (from 2017)

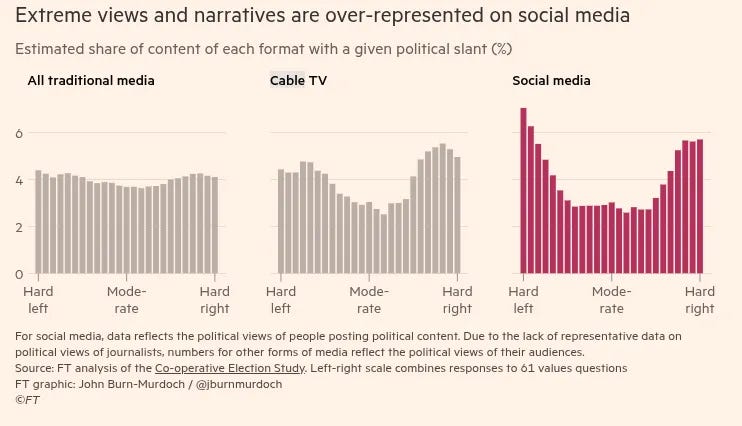

As those two bell curves of left and right wing politics move away from one another, pay attention to the highest point available to the overlap (the purple shape). A valley forms between the blue and red mountains. But I think this is illustrated even more clearly by this set of graphs put out last month by John Burn-Murdoch:

The veracity of these different shapes is almost certainly debatable, but the progression from traditional to social media is suggestive. Moderate politics becomes less and less available, in part because media companies operate with the understanding that extremity pushes engagement. People are losing their jobs over relatively anodyne social media posts, while celebrity comments, ad campaigns, and (bland) logo updates become salvos in our unending culture war. It’s never been more important for our livelihoods to be online, but being online feels more and more like exposing ourselves to its volatility. Avoiding that uncertainty is part of what’s led to the cozyweb. As Maggie Appleton describes it,

We create tiny underground burrows of Slack channels, Whatsapp groups, Discord chats, and Telegram streams that offer shelter and respite from the aggressively public nature of Facebook, Twitter, and every recruiter looking to connect on LinkedIn.

Ai chatbots might provide a similar respite, but with the added benefit of being able to reach beyond the limits of a small, curated community, not to mention the positive reinforcement that they’re designed to provide users. If the uncanny valley is that zone where near-humanity provokes revulsion in us, perhaps the “canny valley” is a space where we can remain insulated from the sturm und drang of our current internet while still availing ourselves of its advantages? As Mollie puts it, “you’re with the machine and that’s all you’re with.”

The Rhetoric of Friction

If I’m right in suggesting that people are turning to chatbots as a type of canny valley, whether it’s to escape real world interactions or online ones, we should nevertheless be clear-eyed about the dangers of doing so. Lila Shroff’s piece for the Atlantic a couple of weeks ago, “Chatbait is Taking Over the Internet,” argues that

As OpenAI has grown up, its chatbot seems to have transformed into an over-caffeinated project manager, responding to messages with oddly specific questions and unsolicited proposals….often, it feels like a gimmick to trap users in conversation.

Even if beleaguered users find in chatbots a safe informational harbor, their hosts are far more interested in positioning themselves as casinos, the House that always wins (our money and attention). “As competition grows and the pressure to prove profitability mounts, AI companies have the incentive to do whatever they need to keep people using their product.” And paying for the privilege of doing so, needless to say.

But there’s an important feature missing from these canny valleys, and that’s friction. Last episode, I briefly mentioned a post from Rob Horning that I want to return to. Horning draws on the work of Adam Phillips, specifically on the idea of resistance, and how important it is for (among other things) therapy. When we’re working out our issues, the value of having another human in the room is that they can help by noticing the things that we don’t notice ourselves, by identifying our blindspots. To put it another way, one of the best part of having friends is that they will call you out on your bullshit. The absence of any sort of resistance is precisely where chatbots fail.

Where analysis deliberately steers toward moments of friction and conversational breakdown, chatbots are implemented to prevent conversations from breaking down and help users overcome their reluctance not through a difficult process of intersubjective negotiation but through “sycophancy” that has been demonstrated to encourage users in their delusions.

Horning concludes by noting that, therapeutically, Ai “turns language into a weapon against communication,” all while that barrage of marketing tries to gaslight us into believing the reverse, that it will make us better communicators, better humans. The “canny valley” is little more than Schüll’s machine zone, offering us the illusion of reliability and calm as it slowly sucks as much value from us as it can.

I could probably double this in length with another day or two (and fill out some of these claims more thoroughly), but I’m going to let this rest. I’ve got a mini backlog with a couple of books waiting to be reviewed, and some other topics I want to write about. More soon.

Sometimes I look back at older work and cringe, but that wasn’t the case here. Some of my citations are very much of the moment, but I think the argument itself is pretty solid.

If you’re not familiar with the family who’s suing OpenAI after ChatGPT assisted their son’s efforts to take his own life, it’s worth looking into. It’s not an easy watch, but Kara Swisher posted a YT interview with the Raines as well.

The phrase “cultural dopes” was coined as a critique of that framing, as a refutation of the idea that the masses were incapable of negotiating cultural messages in sophisticated ways. I use it here to highlight the problem with assuming that “Ai psychotics” are necessarily dopey.

Nowadays, sports gambling ($150 billion dollars of bets in 2024 alone) is probably the bigger story, especially considering how mobile gambling apps are combining the dopamine drip of social media with celebrity endorsement and wealth extraction. And there’s been a real uptick in stories about college athletes being drawn into sports gambling.

Part of the reason I struggled with Vauhini Vara’s Searches was that her Ai-written chapters felt uncanny to me, and I think you can see that in my review of the book.

One of my former digital rhetoric students is now taking professional writing with me this semester and any time we are reading and thinking about anything involving AI or The Rot Economy or aesthetics or really any piece of this shitshow, she's quick to point out that the promise is a life without FRICTION. I think you're right to connect that with platformization training and what people are desperate for NOW/after.

Good heavens. I find myself thinking about Terry Gilliam's 'Harry Buttle, guerilla heating and cooling technician'; and, not unlike Sam, the protagonist - victim of that story, dreaming of having a massive copper rod flung across the substation mains to see hundreds of servers arc-flash into puddles of solder and circuitry.

On the other hand, writers Zitron and Gioia are both foreseeing that this whole dreamworld of the techbros is unachievable. Not enough chips, not enough baseload available, not enough grid capacity, not enough Capital at the rate its being shoveled into the furnaces. But still, they mess with people and their lives. For money. Some say this is looking like an enormous bubble, with investors about to be fleeced. Oh well. Thanks for the lead to Kara Swisher here, too.