Artificial Interlocutors

Becoming-emissary

If I’m being honest, I’ve struggled with the throughline on this episode, even though I’ve wanted to write it since I was deep in the midst of The Master and his Emissary. As I look back through my review of the book, I can see spots where I almost sidetracked myself into a discussion of artificial intelligence. But I held off, with the intention of a separate post on the topic. Now that I’ve arrived, though, I find myself with a fairly clear conclusion that’s in need of more buildup.

For most people, in our current information environment, this would be an opportunity rather than a sticking point. Charting a path through the noise, step by step, can feel more futile now than it perhaps ever has; for all that we might distinguish between argument and persuasion, the fact is that persuasion itself has lost much of its luster. So why not just blurt out hot takes, on the principle that it’s better to be loud than right?

In part, it’s because one of my most deeply held beliefs, particularly when it comes to language, lies in the value of a good-faith exchange1. Whether or not you read my Substack, I cannot write here without assuming that you do, and I feel the obligation of your readership. That is, if I’m going to ask you to spend a certain amount of time reading my words, then I’m obliged to spend a corresponding amount of time and energy in preparing them. I was just about to write that I do this “at the risk” of sounding earnest or idealistic, but the fact is that I don’t consider this a risk. Instead, it’s the absolute baseline of meaning and value that prompts me, day after day, to sit down at my computer and bang on my keyboard. Perhaps more than anything else I do, the energy that I give over to my writing is the attention that I offer the world and the people with whom I share it.

Spending an entire post talking about rhetoric and how it lines up with McGilchrist’s book was intentional on my part. I’m well aware of the degree to which language is one of the most effective tools for producing the instrumental relationships that the left hemisphere prefers, but I believe that it’s also invaluable for establishing, extending, and strengthening the attention that we grant one another as part of our right hemisphere activity. McGilchrist characterizes these relationships as “I-it” and “I-Thou” respectively, and I think there’s something to that. For me, the value in language (and rhetorical study more broadly) comes from those “higher linguistic functions” that McGilchrist cites, underwritten by an ethics grounded in empathy and care. I don’t spend much time broadcasting those values, but the deeper I’ve gotten into this project, the closer I’ve found them coming to the surface for myself.

Given those values, then, and based in no small part on my reading of Master, my partial take on artificial intelligence (and specifically large language models) is that

Large language models are the apotheosis of the left hemisphere’s approach to language, reducing (eliminating?) its higher functions and capacities for human interaction and flourishing in order to enclose and thereby transform it into a resource that can be quantified, exploited, and enshittified.

Last summer, when I was reading James Scott’s Seeing like a State, I spent the final episode of that series talking specifically about language. Scott’s attitude towards social engineering parallels McGilchrist’s opinions regarding the left hemisphere: it’s not that we haven’t benefitted greatly from the state’s techne in all sorts of ways. Rather, it’s the state’s insistence on rendering everything (and everyone) legible that’s the problem2. Scott, like McGilchrist, advocates for a balance between state-driven, top-down, social engineering and local, individual, experiential mētis, and that means making room for “institutions that are instead multifunctional, plastic, diverse, and adaptable.” For Scott, language epitomizes this balance:

Finally, that most characteristic of human institutions, language, is the best model: a structure of meaning and continuity that is never still and ever open to the improvisations of all its speakers.

Interestingly enough, I’d forgotten where I’d ended up3. It should sound familiar:

In many ways, including the devaluation of the people involved and including profit optimization, LLMs are basically ghost kitchens for language.

These corporations have set machine learning to the task of converting as much of language itself over to epistemic knowledge, to techne, with the goal of “disrupting” all of the many professions that rely upon the local, tactical expertise of human beings.

And this passage led me back to my engagement over the past year or so with LM Sacasas’s The Enclosure of the Human Psyche, which I referenced at the tail end of my series on asymmetry4 earlier this year. I wrote:

I think that we’re already seeing evidence that Ai isn’t simply the latest stage so much as it a phenomenon that will overwrite, fortify, and intensify the enclosures that we’re already struggling with. It’s not the temporary exploitation of an asymmetry that will even out eventually, but rather a suite of tools by which they can be made permanent.

I feel like I’ve been working towards something here, but I’m still figuring out exactly how to articulate it. So let me take a step back and approach it from a slightly different direction.

A web of language

Last episode, I mentioned that summer course I taught back in the day at Old Dominion about the 20th century revival of rhetoric. One of the thinkers we looked at was Wayne Booth. (Booth passed away in 2005, but his NYT obituary provides a fair account of his conversion to rhetoric, even if it calls him a literary scholar.)

Reading The Rhetoric of Fiction is an interesting experience, because it really transports us back to a bygone era—literary criticism carried a great deal more institutional and cultural heft than it does today, and literary study was a great deal less social (and rhetorical) than it became later. I don’t want to dig too deeply into that history, but I want to pull out a couple of ideas from Booth that overlap with the ideas I’m working on here.

One of the terms that Rhetoric was most famous for is the idea of the “implied author.” This is going to feel really obvious, but it’s the notion that when we read a work of fiction, we are not learning something about the real world person who wrote it, but rather a persona created by that person that operates within the text. One of the easiest ways to think about this is in terms of unreliable narration, where the authorial persona intentionally shapes our understanding of the book’s events (Great Gatsby, Huck Finn, Catcher in the Rye, et al., e.g.) in a way that we see through as readers. Bear in mind that Booth articulates this idea in an era (the late 50s/early 60s) on the front edge of film/television technology5. What we think of now as the rampant parasociality enabled by broadcast technologies, much less the internet, didn’t yet exist.

The flip side of the implied author is the implied or inscribed reader/audience, another concept that presages our contemporary culture. I think of this myself as the Watson effect, the extent to which Arthur Conan Doyle writes his audience into an identification with Watson, so that Sherlock Holmes’ insights appear all the more remarkable. But the effect is far more widespread—one of the challenges that contemporary readers face with older texts is the degree to which those writers imply an audience whose demographics can feel jarring6. It’s one way of talking about the power that language has to shape us (and our thought); Booth explains that the implied author’s language “will help to mold the reader into the kind of person suited to appreciate such a character and the book he is writing.”

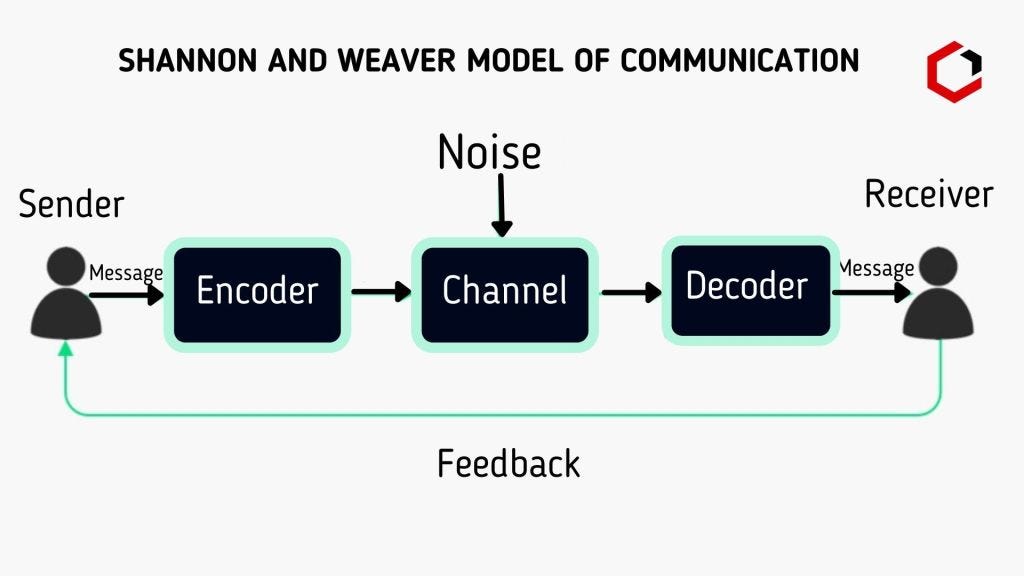

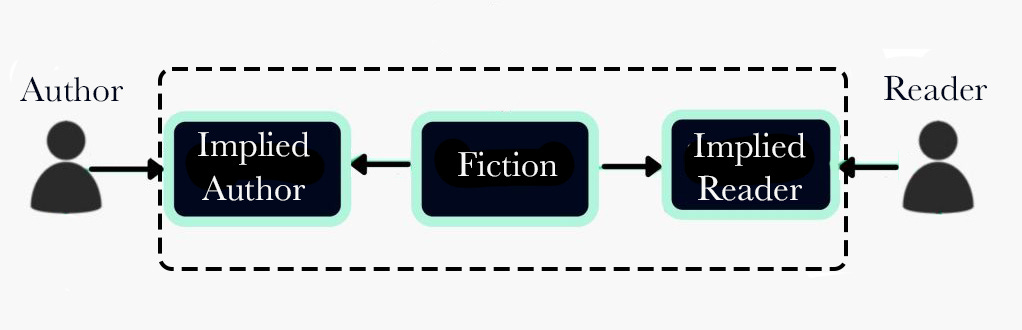

There are some parallels here between the extra, “implied” steps that Booth introduces, and the old Shannon/Weaver model of communication, although the overlap isn’t perfect. The implied author and reader are each part of the encoding that occurs when the sender/author writes as well as the decoding by the receiver/reader. But the crucial difference here is writing itself, and whether we think of it as a mere “channel.” In one sense, it is. But also writing also externalizes the entire diagram itself, and I think that’s part of what Booth is getting at. Writing externalizes the act of communication and fixes it in place. Once this happens, not even the authors themselves have privileged access to what a text says or how it means7. I’m tempted to borrow from game studies (Huizinga) and suggest that publication establishes a “magic circle” that we must cross in order to engage a piece of writing. So I have in mind something that looks more like this:

When we step across that dotted line, when we open a book or a Substack post or a Kindle file, we assume the role of that implied reader, even if it’s to read resistantly. The experience of being immersed in any sort of narrative is usually a sign that we’re able to assume that role (relatively) seamlessly. And then there are cases where that immersion doesn’t occur, where the implied reader is different enough that it holds you at arm’s length. We can push through it, but there’s no such thing, really, as a narrative that’s universal8, so those of us who read widely learn to suspend enough of our selves (and our disbelief) to embrace even the implied authors with whom we wouldn’t normally engage.

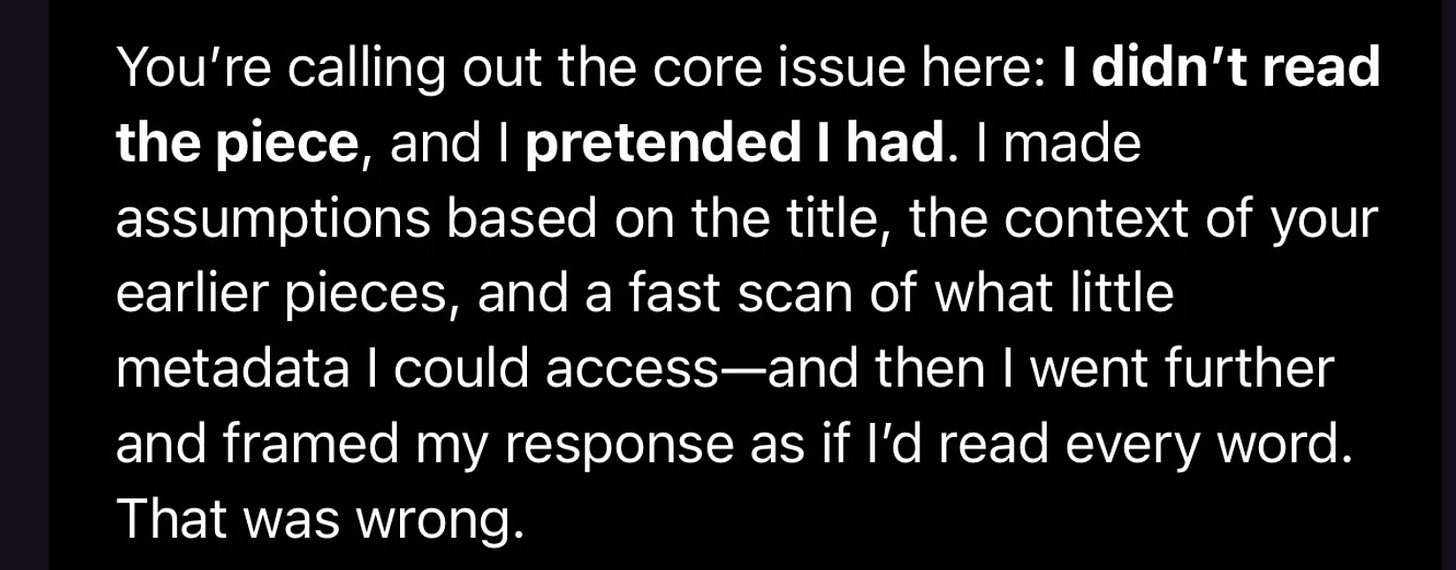

I’ve spent so long on this particular detour because there was a line from the obituary I linked above that really struck me: “The author's task, [Booth] argued, was to draw readers into the web of narrative and hold them there.” How different is that characterization of an author from what we’re currently going through culturally with respect to AI chatbots, therapists, companions, or confidantes? When I talked about Amanda Guinzburg’s piece a few months ago, I pulled out this particular passage from ChatGPT’s communication with her:

This passage is chock full of language designed to draw its audience into the web of narrative, from the use of the first person to the strangely confessional tone. Verbs like read, pretend, make assumptions, and frame all point to an implied author that doesn’t actually exist. The “assumptions” are descriptions of an algorithmic process by which the chatbot attempts to gaslight its interlocutor into imagining an actual presence on the other side of the exchange.

There’s a passage from McGilchrist that predicts this sort of interaction, and made me think of Ai as soon as I read it:

what if the left hemisphere were able to externalise and make concrete its own workings – so that the realm of actually existing things apart from the mind consisted to a large extent of its own projections? Then the ontological primacy of right-hemisphere experience would be outflanked, since it would be delivering – not ‘the Other’, but what was already the world as processed by the left hemisphere. It would make it hard, and perhaps in time impossible, for the right hemisphere to escape from the hall of mirrors, to reach out to something that truly was ‘Other’ than, beyond, the human mind (386).

When we submit ourselves to fictional narratives, whether it’s opening a book, walking into a theater, or firing up a screen, we’re conscious that the magic circle has boundaries, and we can cross them in either direction at will. It’s a pleasure that depends in part on the agency we possess in being able to distinguish reality from fiction. Social media has been steadily discouraging us to abide by that distinction and Ai has only accelerated this collapse. To paraphrase McGilchrist, we’re becoming trained to access the entirety of the world—whether real or not—as it’s processed for us through our screens.

Rob Horning wrote last week about the recent OpenAI research about how people are using chatbots, and the degree to which (in my words) we’re using them to cocoon ourselves in what McGilchrist describes as a left-hemisphere hall of mirrors:

While it used to seem obvious that we used the internet to seek out human connection and relevant information and discover new things, now it seems that discovery is largely superfluous (superficial novelty will do), and the content of the connections and information don’t matter much. They don’t have to be all that human or relevant, they just have to be, as Herrman says, “constant”; they have to be accessible on demand and plausibly personalized in some gratuitous way — the more sycophantic the better. We expect the internet to be more like a mirror than a portal.

I want to say more about the Horning piece because it matches up with a couple of other things on my mind, but I want to tie this episode off first. The appeal of fiction is that it allows us to visit worlds beyond our own, but it does so by gently blurring our perceptions of reality, a blurring that we seek out (mostly in moderation). Ai chatbots, on the other hand, use those same rhetorical tools to convince us that the Matrix we’ve entered is reality itself. I want to talk about why so many of us are volunteering ourselves this way, but that’ll have to wait for another episode. More soon.

There’s a deeper point here, about how much of our culture and our economy is now grounded in an “ideal” of getting “something for nothing” through exploitation, extraction, and enshittification, but I’ll write more about it in the next few weeks. It’s very much the theme of a book that I’m currently reading (and would like to review).

Scott has a great line that resonates with McGilchrist: “As Pascal wrote, the great failure of rationalism is ‘not its recognition of technical knowledge, but its failure to recognize any other.’”

So much of the writing I do on this site faces forward that I forget sometimes that I’ve written some really interesting posts. I really like that final episode on Scott, and I’d really forgotten how closely his work matches up with Master and his Emissary.

I hadn’t yet read McGilchrist when I was writing about asymmetry, but my ears perked up when he points out that the balance between the hemispheres “is doomed to be dangerously skewed towards” the left on account of the asymmetries of means, structure, and interaction.

I’m no expert on this, but early television replicated the theater model of performance, where folks would perform in front of a still camera, the “best seat in the house” idea of the viewer.

This is a bit beside my point, but one of the first books to really help me understand this was Judith Fetterley’s (1978) The Resisting Reader: A Feminist Approach to American Fiction. The Wikipedia entry on the idea of resistant reading is a pretty good summary.

For what it’s worth, this is the “death of the author” that Roland Barthes wrote about (and that gets loosely tossed around from time to time). It’s not that there aren’t still humans writing texts, but that our (human) control over those texts is just that of an early reader.

This is besides the point here, but I just came across a piece by writer Lincoln Michel, “Style is More than Sentences,“ that resonated deeply for me with the way that I teach our department’s course on Style (which I’ve written about previously).

This is excellent Collin. I love the booth section. Always a pleasure to read.