Asymmetry (part 4)

When Google killed blogs

(This is the fourth part of a multi-part series, so you may want to visit Part 1, Part 2, or Part 3)

I’d originally planned on spending this episode talking about some of the issues that exist with social media, but I think I’ll put that off for at least one post. There’s a transitional moment in that history that I want to revisit, one that actually precedes the development of social media sites/networks as we now understand them.

I talked about the interplay between search and spam in my last episode, and the role that weblogs played in that eternal struggle, but there’s at least one more disruption worth exploring that emerged during that time, and Google played an important role there as well. Wikipedia has a nice history of weblogs, which I won’t recount here, but I think it’s important to note that, as search engines began to automate and aggregate the web (which itself was growing exponentially), the human curation that once characterized Yahoo! didn’t vanish. Instead, it changed form, and weblogs were one of the places where it re-emerged. That wasn't blogs’ only purpose, but it was pretty crucial.

Websites, including both corporate sites and personal homepages, had and still often have "What's New" or "News" sections, often on the index page and sorted by date….Early weblogs were simply manually updated components of common websites….Blogging combined the personal web page with tools to make linking to other pages easier — specifically permalinks, blogrolls and TrackBacks. This, together with weblog search engines enabled bloggers to track the threads that connected them to others with similar interests. (Wikipedia)

In part 2 of this series, I mentioned (via Julian Oliver) the ways that that we tend to rely on our mythic imagination to characterize our technologies, and in some ways, the introduction of accessible blogging software introduced a fork in the road for internet culture (or amplified one that was already there, more likely). We still use the language of “pages,” even where it’s not exactly true, to talk about the screens that show up on our phones and computers, and early attempts at organizing the web relied on systems borrowed from libraries. A page is relatively static, a repository for written information, knowledge, or expression, something that we read (and remember, or shelve, or discard). The metaphor of the page is different from that of the site. A site is a place, and a great deal of the mythic language surrounding the internet in the 90s (virtual reality! information superhighways!) was pitched towards convincing us of the net’s place-ness. Places are more dynamic—we visit them, hang out, maybe even interact with other folks there.

In the early days of browsers, one of their features was the ability to set your homepage, the website that would load by default when you opened them. This was part of the motivation, in my opinion, for the addition of “News” or “What’s new!” sections on otherwise static homepages—they were rewarding site visitors who otherwise had no reason to keep returning1. The rest of the page, though, remained static, and at a time when most of us were still on dial-up modems, the prospect of loading graphics-heavy, static pages, in order to check a small, dynamic corner of updated news never felt especially convenient.

In some ways, then, weblogs were a remediation of the “News” sections of an otherwise static website. They also tapped into a range of other genres: online diaries, commonplace books, and the sense of human curation that had become crowded out through automation. In other words, weblogs incentivized a much more social understanding of the web. It was no accident that “social software” (the terminological precursor to social media) emerged in the early 2000s, just as blogging platforms like Blogger and Movable Type blossomed and sites like Flickr and Delicious emerged. The web was no longer exclusively about accessing information and/or commodities; it was developing into a place of its own, one where social networks were beginning to form.

(Personally, this was the stretch of time where I first began getting interested in network studies. Albert-László Barabási’s Linked came out in 2002, and Duncan Watts’ Six Degrees was published a year later. The different tools that emerged around weblogs—web rings, blogrolls, trackbacks, comments, et al.—provided readers and writers not only with a variety of ways to engage with one another, but they made those connections visible in a way that traditional media could not. The blogosphere concretized network studies for a lot of people2.)

But it also created something of a tension for Google. On the one hand, blogging software made web publishing exponentially easier and more accessible. There was no need to learn HTML, CSS, or FTP—in this sense, content management systems (CMS, the more technical category that included blogging platforms as well as the nascent website-in-a-box products that were emerging at the time) democratized access to web publication. This proliferation of sites had a couple of effects. There was a lot more writing that existed outside of the ecosystem upon which the original search engines were based. There’s a difference between searching for information (measured by accuracy and relevance) and searching for something interesting to read and engage with. The latter is often a more social category, and involves trust.

The ease with which hyperlinks could be deployed also complicated that original model of search. This was an era where folks could still, through some concerted effort, link-bomb to skew Google results3, and as I mentioned in my last installment, the comments sections on weblogs were often abused by search engine optimizers to do the same. I’m fairly sure that this was the point where Google really began tinkering with their algorithm—while I don’t doubt that the original purpose of their manipulation was a concern for accuracy, it eventually led to the sloppified zombie site that continues to dominate “search.” But there’s a smaller story to be told about Google’s response to the blogosphere, and that’s the tale of Google Reader (nee Fusion).

As the blogosphere expanded, with more and more people began publishing blogs, an obvious problem emerged. If you’re “following” dozens (or even hundreds) of frequently updating sites, the prospect of visiting each one (and hitting reload to see if there’s anything new) probably sounds exhausting. And it was. Fortunately, though, there was an easy, non-proprietary solution. Weblogs themselves aren’t “pages” in the traditional sense—the homepage for a blog was actually a generic container, filled with data from the CMS database (in much the same way that Google results or Amazon pages do the same thing). When you visit a blog’s “page,” it fills that container with the most recent information from the database. It also creates the possibility for syndicated feeds (RSS stands for Really Simple Syndication) and what came to be known as aggregators. An aggregator is a piece of software that can do a variety of things, but the easy explanation for our purposes is that it’s a client that can “subscribe” to lots of sites, and check them every so often to see if there’s new content. Think of it this way: each blog post comes with a timestamp, data which is also stored in the CMS database (and published on the page next to it). An aggregator can simply ping the database to see if the most recent publication date is the same as the last time it checked. If it’s not, then there’s a new post, which it can download. In many ways, then, it was much like an inbox for weblogs. Instead of going from site to site to see if it’d been updated, many of us who followed large numbers of blogs could just check the aggregator and read the post there, or visit the site if we wanted to leave a comment, etc. It also allowed you to bookmark/star posts, share them with other folks, etc.

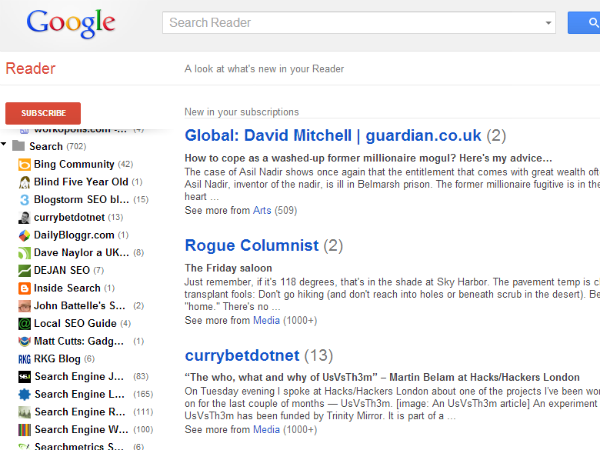

In the early 2000s, aggregators were just coming into vogue. For a while, I used one called Bloglines, which was named one of Time Magazine’s top 50 websites in 2004. But it didn’t last long. In 2005, Google stepped in, and released an aggregator that was originally supposed to be called Fusion, but eventually was released under the name Reader. Not only did it draw on the same UI that GMail (which came out in 2004 to incredible acclaim) used, but it was backed by a pretty talented group of engineers4. In a very short time, it became the most popular aggregator by far, virtually monopolizing the space. At its peak, Google Reader had nearly 30 million users.

As the Verge retrospective on Reader explains, though, “That’s a big number — by almost any scale other than Google’s.” And Reader eventually suffered for it. Because the team responsible was using their off-time to support it, and because its value was largely opaque to the company’s decision makers, Reader didn’t receive a great deal of internal support.

“To executives, Google Reader may have seemed like a humble feed aggregator built on boring technology. But for users, it was a way of organizing the internet, for making sense of the web, for collecting all the things you care about no matter its location or type, and helping you make the most of it.”

Although Reader was retired officially in 2013, the writing was on the wall well before then. It entered “maintenance mode” in 2011; technically it was still available, but they weren’t actively developing it. As the Verge piece explains, “the real tragedy of Reader was that it had all the signs of being something big, and Google just couldn’t see it.”

What they saw instead was Facebook, and eventually Twitter. According to a piece about Google Reader on the site Failory, “Google was changing its role from a ‘portal’ for the user visiting other sites to a system aiming to keep users engaged while delivering content to them.” Despite the best efforts of the folks involved with Reader, Google execs saw it as a “side project” that compared poorly with social media platforms, even as those new walled gardens were themselves being used by millions of people for the same sort of social curation that they’d already been practicing through Reader. Instead of investing in Reader and building it out into something that might compete with other platforms, Google let it languish and ultimately die, devoting their energy to ill-fated social media knock-offs like Buzz and Google+.

It’s easy to forget that social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter were once pitched to us as “microblogging” sites—the term itself died alongside the blogosphere. While it’s probably not entirely fair to lay the blame for those deaths at Google’s feet, Reader was a crucial part of the infrastructure that millions of people (myself included) relied upon to navigate that nascent social space. There was a handful of off-brand aggregators, but they weren’t as good and none of them ever really acquired a critical mass of users5. And because Google had let Reader simply sit there for years past any sort of active commitment to it, a lot of folks (including bloggers themselves) had already migrated to social media. Whether they were the final nail in the coffin or not, Google’s neglect of Reader certainly accelerated the shift to platforms.

The irony of it all is that, 20 years later, many of us have built our own bricolage of tools (Delicious, Pocket, Instapaper, Evernote, Readwise, Zotero, Sublime, Obsidian) to approximate what Reader was already accomplishing back then. “…you can see in Reader shades of everything from Twitter to the newsletter boom to the rising social web.” A lot of the success of Substack itself is a renaissance of that 2000s energy, before social media decided to foreground the interaction (and chaos) of comment sections and focus exclusively on cramming us all into the one-size-fits-trolls spaces that dominated the 2010s.

I’m afraid this post has wandered quite a ways away from my original frame of asymmetry, and I’m not sure it’s worth the time to try and steer it back. In the same way that blogs took a piece of then-common webpages (the frequently updated News section) and remediated them, social media platforms ultimately did the same to blogs, turning the comment sections into the never-ending algorithmic feed. (and the way that TikTok did the same with video swapping on FB/T, for that matter.) So I do have the sense here of online culture achieving brief moments of equilibrium only to face disruption. And I do think that this particular episode represents a fork in the road where one set of values ends up erasing another (to users’ detriment), but framing it as asymmetry doesn’t quite fit for me6.

I’m going to keep pushing forward, though. I think my next post will talk about social media in particular, and the emergence of clickbait, which builds on some of the stuff I discussed in part 3. More soon.

It’s the same logic behind putting out shelves and tables of bestsellers and/or new releases at the front of the bookstore rather than expecting customers to excavate them from their individual sections.

Once upon a time, I even wrote an academic article about this. In 2005, I’d taught my first graduate course on what I was calling “Network(ed) Rhetorics,” and in the piece I’ve linked here, I suggested that what was then called social software would mark a “new paradigm” for technology. Twenty years later, that probably counts as one of the most prescient things I’ve ever written.

Culture warrior review-bombing on sites like GoodReads, IMDB, Rotten Tomatoes, or Yelp (whether to lift up or screw over folks) remains a frequent tactic to this day, and limits the usefulness of those review services.

A couple of years ago, The Verge published a retrospective on Google Reader on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of its demise. It’s a great read, and the place where I get some of my tone from here.

There’s an interesting parallel here to the way that Mastodon, Bluesky, and others have failed to recapture the audience once committed to Twitter.

For reasons too long to go into, I think that this was a key moment in the secret war between the metaphors of ecology and platform for the hearts and wallets of internet users. It may also represent the death knell for the kind of emergent online culture that was so prevalent in the 2000s, the optimistic, pro-democratic, weak-tie social capital model that many in my generation grew up on.