(This is the third part of a multi-part series, so you may want to visit Part 1 or Part 2)

For multiple reasons, I haven’t had a great deal of spare brainspace to read or write, so this series has been slower going than I’d originally planned. But if Part 2 of this series was intended to be the “onramp” to the asymmetries of online culture, this episode will try to zip through a few different examples. I’ve talked about how, more and more, the development of that culture feels less like a smooth arc of progress to me, and more like a series of short, semi-stable developments punctuated by longer periods of disruption. That disruption, more often than not, is driven by those who exploit informational asymmetries, converting them into power, resources, access, etc.

Much like the metaphors of mail and addresses conditioned the way that we think about email, the metaphors of page and site affected the way that we approached the web. They imply a stability and location that was once (more or less) the case; while I’m not going to tease this out too much here, I think it’s worth mentioning.

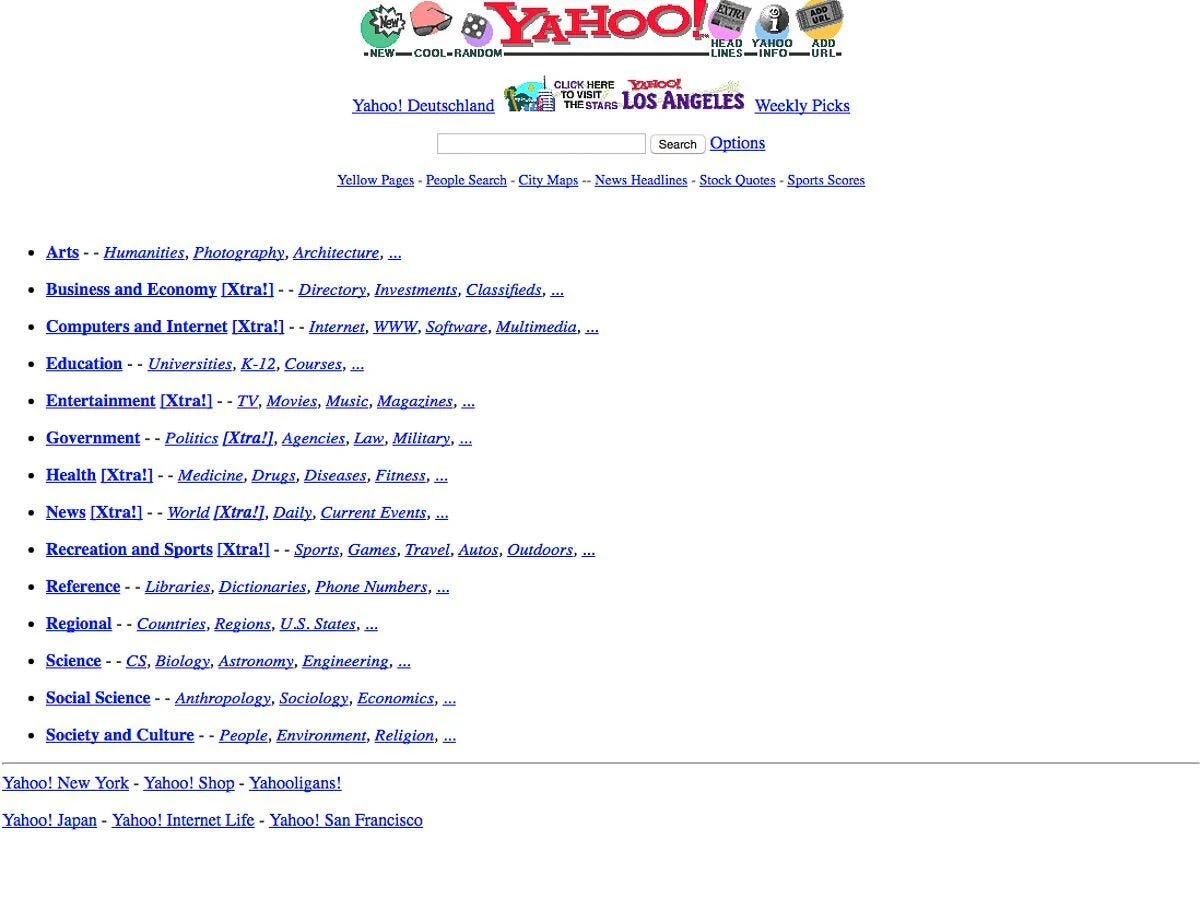

I was lucky enough to get into web design on the ground floor - my friends and I created homepages and websites just as the earliest (visual) web browsers were emerging. Netscape released Navigator in 1994, the first year of my PhD program. For several years, I was attuned pretty closely to web development—if I’d wanted to, I could probably have left academia for a web dev position in industry.1 In those early years, when folks were still imagining what the web might eventually become, Yahoo! emerged as the first high-profile search tool2, and I mention “pages” above, because Yahoo! was organized and functioned much the same way as a library was/did. Eventually, the web began to grow much faster than Yahoo! could cope with, but in the 90s, if you wanted folks to find your pages, you needed to get them onto Yahoo! That involved finding the best hierarchical directory for your site, determining the person responsible for that section of the site, and submitting your URL and a 1-sentence description for their approval (and ideally, inclusion on the site).

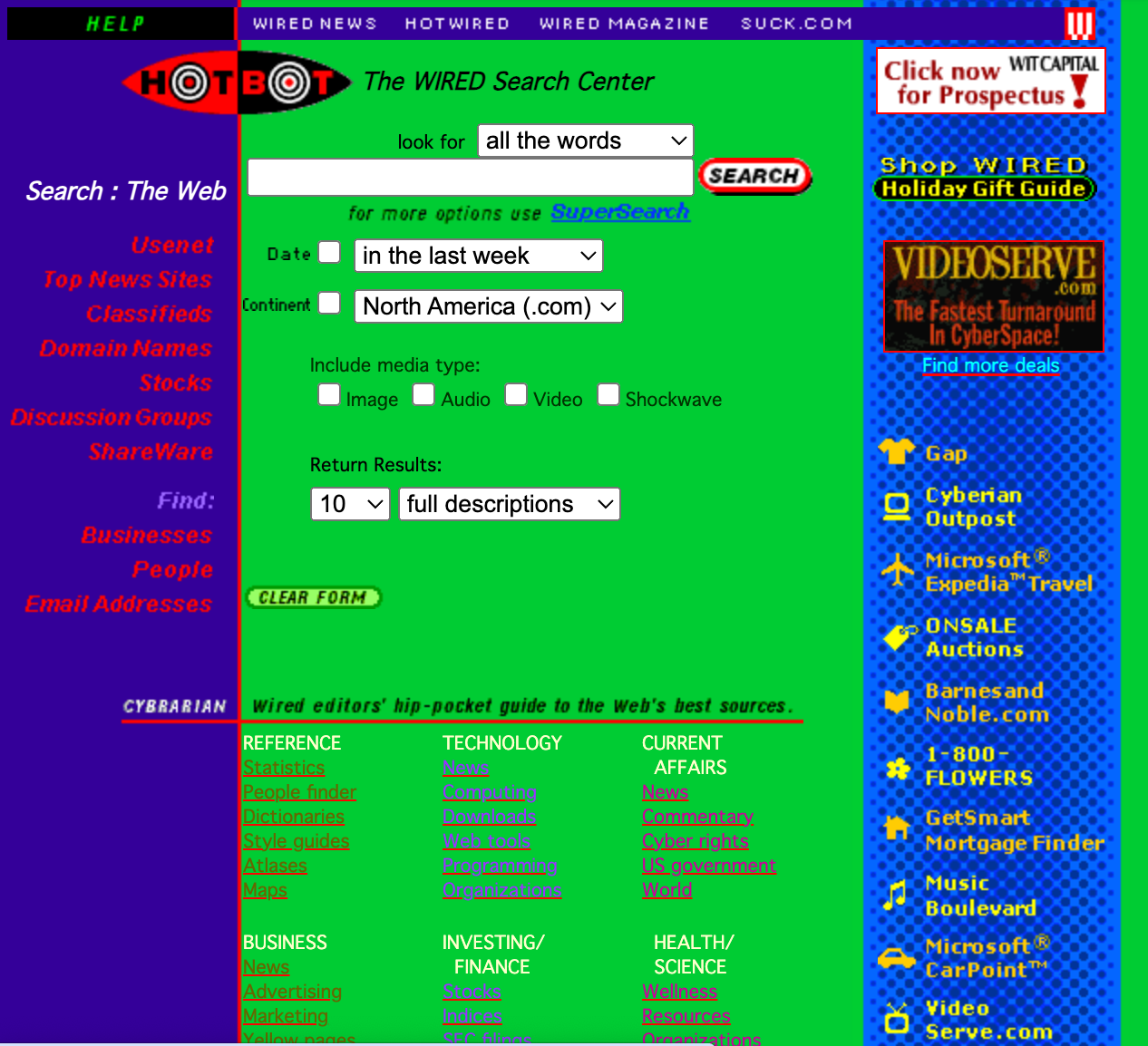

Although we make a big deal out of automated text-processing with AI, the shift from human curation of web directories to search engines was a major step in this direction. It also inaugurated the (forever) arms race between search tools and the shady business of search engine optimization. Once web crawlers began to take on the burden of reading the pages themselves, they invoked their opposition, so-called experts and gurus who promised to game these systems on behalf of folks who wanted to place their sites at the top of our search results. This was the brief era of Alta Vista, Hotbot, Lycos, and other search engines.

I’m working from distant memory, but most of the search engines at the time tried to strike some balance between engine and directory. The results, as you can see above, were kludgy and crowded pages. Google’s emergence (and rise to dominance) in the early 2000s had almost as much to do with the clean appearance of the site as it did with the engine behind it.

While the SEOptimizers of the era were encouraging web writers to pack their pages with misleading, invisible keywords3 in order to trick the webcrawlers into misreading relevance, Google was mainstreaming PageRank, a new way to measure the relevance of webpages. Rather than crawling a page for the number of times a topic appears on a page, PageRank used the hyperlinks between page to determine its importance. Although this process took some time to sink in, what happened was that links shifted in character; they began as tools for connecting one page to another, but with the emergence of PageRank they turned into implicit endorsements.

ETTO: an interruption

Before I go any further, I want to interrupt myself to recognize that this “arms race,” between search providers and SEOptimizers is a case where asymmetries are exploited on both sides, and ultimately feed into each other. Each side is “cheating,” trying to provide a shorter cut to its goals, whether it’s to attract viewers to its site, charge others for their services, etc. As soon as the web outgrew its initial efforts at human curation, this cycle began. As I’ve been writing the past couple of years, I’ve become more and more convinced of the importance of Goodhart’s Law4, which I’ve written about before.

I thought about this a bit when I came across this piece at Protocolized, about the Efficiency Thoroughness Trade-Off (ETTO). They explain that

Efficiency and thoroughness are both valuable characteristics, but are fundamentally opposed. Erik Hollnagel, a prolific safety researcher, dubbed this the ETTO Principle, short for Efficiency Thoroughness Trade-Off. It’s impossible for an individual to be maximally efficient and thorough at the same time.

With the introduction of automated web crawlers, the search biz looked for an efficient shortcut. Rather than actually reading a webpage, the crawler would process the page for keywords (and this is where Goodhart comes in), and take that accounting as a disconnected measure of the page’s meaning. Rather than writing pages organically, the optimizers would turn that measure into a target, learning that it was more efficient to just pack a page with slop in order to game the crawlers.

I’m still thinking about how to describe how Goodhart’s Law and ETTO fit together conceptually, but I’m relatively certain that they do. If the latter is a broader fundamental law, then perhaps the former describes individual operations as people or organizations attempt to thwart it? I’m not sure yet, but they’re connected, and both have something to do with the flaw at the heart of unlimited scale.

Anyhow, PageRank powered Google’s efforts to render search even more efficient. Rather than reading the pages at all, they could just rely on the assumption that people would link to pages about a given topic in good faith. Links alone became the measure of a page’s relevance or importance, no reading required.

You might notice that I snuck in the phrase “in good faith” referring to the assumptions behind PageRank. And that might tell you what happened as the arms race progressed. Google’s path to search monopoly happened at roughly the same time that weblogs (and the tools to manage them, like Blogger, Movable Type, et al.) emerged as a web genre. I don’t want to spend too much time on weblogs, except to note two small things and one larger one. Weblogs were in many ways a pre-cursor to social media5 in that they helped the web transition from its status as a read-only medium to one where interaction was the goal. Weblog software was also one of the early stages in the development of platform dynamics. Until that point, at least for individual users, creating homepages was something that we did by hand. It was probably around the mid-2000s where I stopped doing course webpages myself, and started using platform tools6.

Those are minor points, though, for my purposes here. One of the chief features of weblogs (beyond its conveniences for writers) was the ability to leave comments, to engage with not only a writer but a larger community of readers. Those comments allowed you to sign them with a linked email address and initially, at least, to include links in the body of the comment. Perhaps you see the problem? All of a sudden, the proliferation of comment sections gave anyone the power to add links to your webpages, and the effort it took to copypaste a link was far less than the energy and effort required to moderate an active comments section. And that’s to say nothing of all of the one-and-done blogs out there that basically turned into spam factories, flooded with junk comments on long abandoned posts (before the platforms developed the tools to fight them). The explosion of comment spam in the early 20-oughts turned PageRank into a mess, although I think it took a while for folks to understand this generally.

By then, Google held a near-monopoly on search (one that they continue to invest billions in maintaining), but the typical results page became less a reliable source of information and more a scoreboard for SEO creeps. And that’s before the hardcore enshittification took place, where it became pay-to-play and Google’s leaders were intentionally sabotaging their product (and wildfiring their workforce) in order to extract more profits from it. That’s really been the past 5-7 years or so—I’ve written before about the way that Google has been working to purge the last vestiges of usefulness from its results, doing everything it can to wipe out content that isn’t generated by AI-powered slop farms willing to pay them for site placement.

For me, search makes for a salient example of internet asymmetry. It becomes really easy to forget that it has its basis in the very human activities of recommending and sharing: here’s an article about X. As the search vs spam arms race continued, though, both sides chipped away at the fundamental value of that exchange, to the point where it’s become “here’s a marginally relevant advertisement that a corporate site has mocked up to game our system, and maybe it’ll help.” Anymore, search is the ephemeral side-effect of an eternal struggle between indexers and advertisers, each trying to outscheme the other.

I think I’ll probably write a bit about social media for this series, and that might just take me to the original set of ideas with which I began it. (I know! 2 months later…) I’ll get there. More soon.

I don’t know the exact moment where that changed, but it was probably in the early 2000s. I was still working at a fairly high level in my first few years at Syracuse before it became too difficult to stay current.

If I’m being technical, Yahoo! began as a search “directory” rather than a search engine, which typically refers to a site that gives users the ability to search the indexed results of an automated web crawler. Directories, on the other hand, were often curated by humans.

Some search engines would rank pages higher for a given topic depending on the frequency with which the term was used. Not only did this affect the quality of the writing on those pages, but one trick was to pad on a bunch of “invisible” text (where the text was the same color as the background) that artificially increased the mentions.

Follow my link, and you’ll find me talking about how SEO is a great example of Goodhart’s Law, which holds that “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

Social media probably deserves its own episode, so I’ll probably cut this one off and discuss it separately.

At the time, the argument was that this democratized access, these platforms that allowed folks without any HTML or CSS to create pages. Back then, platform meant something more like software tool. And there’s something to that, in the same sense that we (mostly) all have access to Facebook or Twitter. But as platforms feudalized (as corporations learned to extract and enshittify), they became about as democratic as the local Walmart. But that’s a whole different story.