You can get with this or you can get with that

Metonymy, continued

{This is a slightly older post that I’d been working on last month. It needed a little transition work, and probably could use a couple more paragraphs, but I’m working on clearing some backlog… -cgb]

A while back, I referred to the idea that our political language has been “metonymized.” While it makes sense to me when I say it, I thought I’d unpack it a little here. I’m hoping to write about this in the book project and I don’t think it’s necessarily intuitive for folks who are less steeped in rhetorical terminology than I am.

One way of thinking about this has become popular in recent years, and that’s polarization, the idea that the overlap between political parties (and their members) has decreased, leading to more ideological extremism, antipathy towards anyone who doesn’t share one’s own beliefs, and in many cases, I’d argue, a rise in anti-democratic legislation.

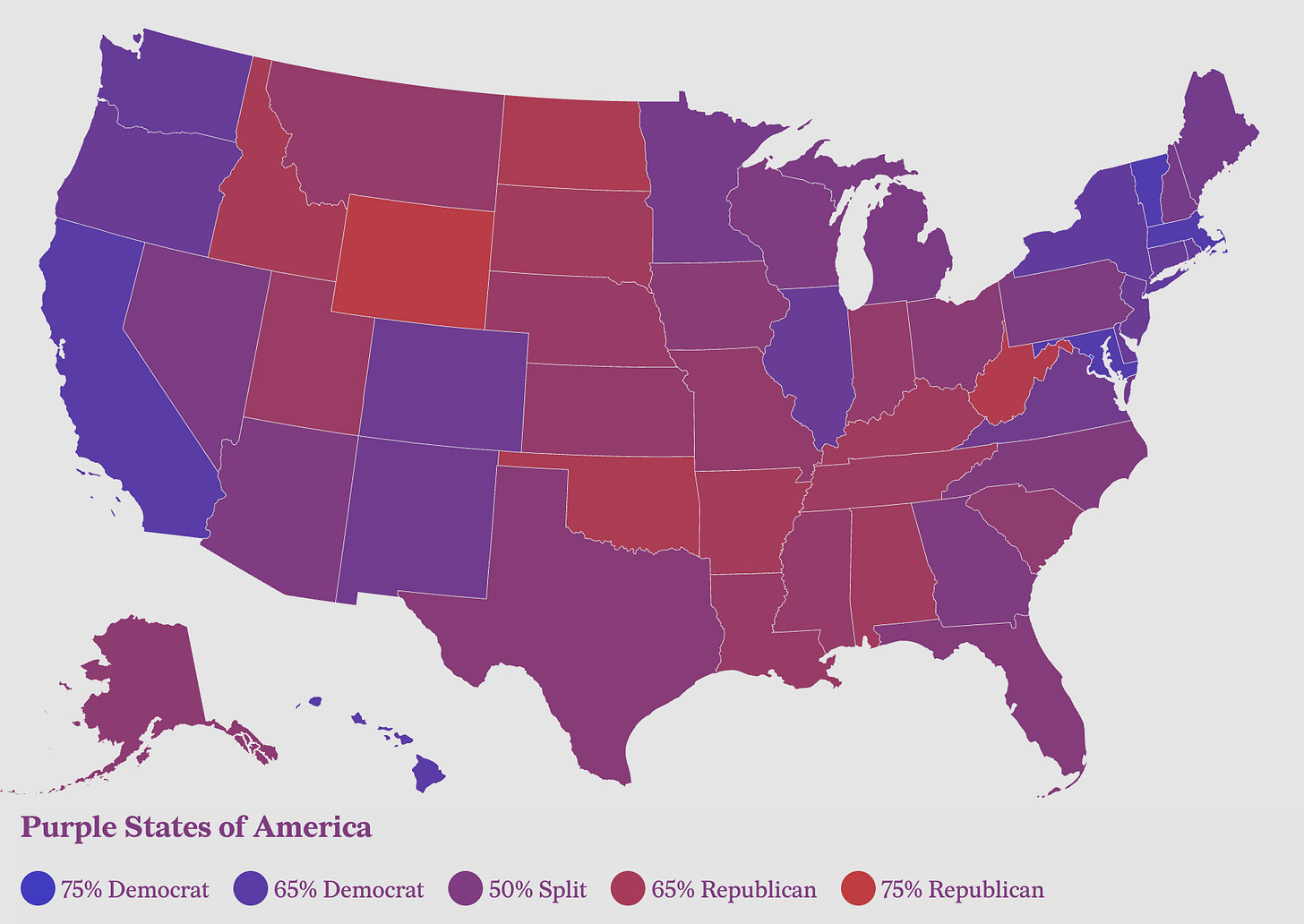

Polarization has been a frequent diagnosis in recent years, but the image above comes from a Pew Report that’s almost 10 years old now. I’ve also seen graphs that stretch back 40-50 years documenting how Congressional voting has steadily come to embody a similar pattern, party line votes and increasingly rare overlap.

I’ll be honest—I’m pretty skeptical of this claim, even given the evidence in that Pew Report and elsewhere. One of the things that they noted ten years ago was that this polarization was driven by loud voices at the extremes, that folks who didn’t see themselves represented by one extreme or the other were more likely to become disaffected and disengaged from the political process. The more that any sort of viable centrism begins to vanish, of course, the more polarized the landscape comes to appear—polarization becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

So what does this have to do with metonymy, a trope that relies on association and proximity, especially when polarization claims that we’re drifting further apart? One potential answer to this is the horseshoe theory of politics, which would hold that opposed extremes actually tend to approach one another as they extend further outward. There’s nothing particularly “correct” about using the metaphor of a line to chart ideological preference, after all.

But I’d contend that it’s the way that, often, two (and only two) positions are framed to us. At the same time that the problems facing our nation and our culture have grown more complicated and intricate, the solutions presented to us by our politicians and media have encouraged us to think of them as “either/or” problems devoid of the nuance that is necessary to them. And this is a problem that has its roots in phenomena that have been with us for much longer than social media (although there’s a case to be made that the internet has amplified these trends).

I’m thinking here of what Jay Rosen describes as the “view from nowhere” style of journalism, a phrase that he borrowed from Thomas Nagel, who wrote that

human beings are, in fact, capable of stepping back from their position to gain an enlarged understanding, which includes the more limited view they had before the step back…To Nagel, objectivity is that kind of motion. We try to “transcend our particular viewpoint1 and develop an expanded consciousness that takes in the world more fully.”

But there are limits to this motion. We can’t transcend all our starting points. No matter how far it pulls back the camera is still occupying a position. We can’t actually take the “view from nowhere,” but this doesn’t mean that objectivity is a lie or an illusion. Our ability to step back and the fact that there are limits to it– both are real. And realism demands that we acknowledge both.

Rosen’s critique of journalism was that objectivity, in many newsrooms, turned into that view from nowhere. Add to this the trend of “debate journalism,” and the view from nowhere holds that opposing positions must be given equal voice whether or not a more realistic perspective would agree. After all, you need two positions to have a debate. And debates are only engaging to an audience if there’s a winner and a loser—the goal isn’t to arrive at compromise or nuance. God forbid that your position might change given a different context or changing circumstances—that would be waffling!

Giving equal voice to disproportionately realistic options and “leaving it to the viewer to decide” in an effort to appear unbiased is irresponsible, in my opinion, but more to the point, it incentivizes a culture and a discourse that places more importance on “winning” than on arriving at the best course of action. And I think we see a lot of situations where our leaders—it’s hard for me not to put that in scare quotes—seem far more intent on running up the score than they are in addressing our nation’s problems.

[Last month, Kirsten Powers (formerly of Fox and CNN) started up a Substack, and her piece about how “Being on TV was bad for my mental health” is a worthy read, and relevant here. In particular, consider this account of so-called journalism: “In D.C., people often note when someone “doesn’t get the joke.” By that, they mean a person who takes things too seriously. People who “get the joke” know that arguments on television are theater, and then you go for drinks with the person you were just in a screaming match with. People who “get the joke” don’t take what’s happening in politics too seriously. They treat it like a game.”]

The shorthand of red states and blue states is a perfect example of this gamesmanship, and a great example of how deeply this problem is ingrained in our culture. The Electoral College, a system developed in the 18th century for facilitating our national elections, is outmoded and ridiculous. But it will never change, for the same reason we will probably never establish term limits for Congress: election winners will never change the rules to make it harder for themselves to win (quite the contrary). Despite the fact that it’s perfectly possible to cast, tally, and report votes almost instantaneously, the Electoral College takes those votes and (mis)represents them into one of two results corresponding to the political parties. And the language surrounding this process—turning a state one color or the other—abstracts us even further from what should be its real-world consequences. There’s a term for this, too—”horserace” politics is what you get when the coverage (and the culture) is more interested in the “game” of it than the actual results. It’s nowhere (in more than one sense).

One way of thinking about metonymizing language, then, is to pay attention to the “shorthand” we use to capture complicated ideas. Kenneth Burke’s term for metonymy is “reduction,” which works well here also. The more complicated an issue is, the more nuance it requires of us to understand, the more tempting it is to try and reduce it to a binary choice, so that we can park ourselves on one side or the other. Metonymy is that trick we see in courtroom procedurals, where an aggressive cross-examination demands a yes or no answer to a question that doesn’t have one.

(Part of what’s challenging about this is that we need those shortcuts, too, sometimes. Associative thinking is part of our toolkit—without it, we wouldn’t be able to function in the world. Imagine trying to arrive at a conclusion only after considering every possible factor, outcome, or consequence, and multiplying that by the number of decisions we make on a daily basis. Metonymy is part of what keeps us from paralysis.)

But it’s also tactical, and that’s more what I’m getting at here—our tendency to reduce nuance to binary choices as a means of forestalling dissent. Or our willingness to grant fringe (and/or bad faith) positions equal gravity with the perspectives they’re attempting to sabotage. Neither of these should strike us as particularly healthy ways to conduct public discourse.

And I could just as easily be describing a platform like Twitter when I talk about the flaws of metonymy. Perhaps more than any other social media space, the birdsite pioneered and popularized the flattened social feed (as opposed to say, nested comment threads on FB and Reddit). And it’s also been instrumental in normalizing social media scoreboarding (followers, views, likes, reach, reposts, et al.), one of the driving forces behind a booming content industry. It’s little wonder that Twitter was so successful in its heyday, and why we still see tweets in advertisements and on news programs—it’s literally a machine for generating and pushing views from nowhere. Journalists didn’t need to bother reading longer texts or conducting interviews in order to synthesize, select, and/or condense a longer discussion into a bumper sticker they could slap on their stories. Twitter was a perpetually-stocked vending machine full to the brim of fun-size, context-free, hot takes.

Its popularity, though, was a symptom of a deeper issue, or perhaps an accelerant. It’s likely no accident that some of our most successful politicians are those who appear unable to string more than a couple of sentences together, unwilling to hold principled positions, and incapable of articulating a positive vision for the country outside of meaningless slogans and hatred towards their opposition. It’s not entirely the fault of metonymy, but our discourse’s hard turn towards associational thinking (and speaking) has played an important role in the impasse that many of us feel.

I don’t want to break up the flow, but I will note that this idea bears a strong similarity to what Kenneth Burke means by dialectic, and he uses the language of transcendence to describe it as well. It’s the ability to perceive the partiality of one’s own perspective (without necessarily abandoning it relativistically).