Like a lot of people, I suspect, I just couldn’t bring myself to bear witness to the MOST GLORIOUS CELEBRATION OF GREATEST AMERICAN PRESIDENT EVER, otherwise known as the televised Cabinet meeting at the end of April to mark 100 days of the current regime1.

Dipping in and out of social media did allow me to witness a few of the breathless, bootlicking highlights, but the experience was much like probing the edges of a wound to see whether it was healing. I could only bring myself to dance around the edges, honestly. Even so, this rare opportunity to peek inside the bubble of the reality distortion field revealed something like the MirrorWorld inverse of a celebrity roast, a performance so relentlessly cringe that it called to mind comparable achievements by other world “leaders.” Like the time that Kim Jong-Il, at the age of 52, shot 38 under par on a championship golf course, the first time he ever played the sport (11 holes-in-one!). Or 66-year-old Vladimir Putin’s ability to score 8 hockey goals, against a team of former NHL players. Or our own mad king’s claims, year after year, of winning his own club championships in golf2.

Maybe the main reason that I paid attention to the farce, though, was something to do with having read Sarah Wynn-Williams’ book on the culture at Facebook. As I was sorting through my notes in preparation for the review I wrote, I kept coming back to the episode that Wynn-Williams narrates about that plane ride to Peru. For all of the horrible things that FB has done (and continues to do), Zuckerberg’s naked emperor moment (for me, at least) is his inability to lose at a board game without accusing the winner of cheating.

I own the games (Ticket to Ride and Catan) that they played, I’ve played them a bunch myself, and I’ve taught lots of people to play them with me. Part of the reason why games like these are popular (besides their relatively casual learning curve) is that they offer an optimal mix of strategic variety and randomness. That is, board games like these offer multiple paths to victory; even if one player is dominating a particular path, it’s possible for other players to be competitive by taking other paths. But randomness is also important. In Ticket to Ride, your destination cards are random. Catan relies a great deal on rolling dice. That means that you can be the most experienced player of these games and still lose, if those random factors don’t go your way. There’s certainly some strategy involved, so experience and familiarity can matter, but those games also have provisions (blocking rail lines, trading more freely with some players rather than others) that allow players to sabotage one another. If you want to keep a particular player from winning, and you’re willing to work with others to achieve that goal, it’s very possible.

In other words, there’s no way to be “the best” player in such a way that you would always win, unless it’s to play only against folks who just aren’t that familiar with the game (which is its own form of rigging the outcome, I suppose). As I’ve talked about before, I’ve played 100s of games of Wingspan, and the vast majority of those against my brothers, who have just as much experience as I do. I’m very good at it, but so are they. And so I’ve lost 100s of games of Wingspan, because the birds we have access to are determined randomly (and in part by turn order). Sometimes a board will just come together for me, while other times, I’ll set myself up for a particular win condition only to not be able to get the right birds to follow it through. Sometimes I’ll feel bad about losing. Sometimes I’ll accuse one of them of hacking Steam to rig the deck (not seriously). As anyone who’s ever played these sorts of games regularly will likely tell you, you’re going to win some, lose some, and the ratio between those outcomes doesn’t really matter, because the point is to hang out and play. I don’t play in order to win, but because I have a decent chance to win, in any given game.

Gamesmanship

There’s an obvious connection between Zuck’s poor sportsmanship and our contemporary political scene (the mad king’s obsession with re-litigating an election whose outcome, while moot, he didn’t like). But that’s not the only reason I’ve been thinking about this. A little more than a week ago, Henry Farrell posted an essay about “Brian Eno’s Theory of Democracy,“ where he cites political scientist Adam Przeworski’s book, Democracy and the Market. The first chapter of that book contains an idea, a formulation of democracy, that has shaped a great deal of the political science that followed:

Przeworski’s theory starts from a simple seeming claim: that “democracy is a system in which parties lose elections.” It then uses a combination of game theory and informal argument to lay out the implications….This is a more beautiful idea than I am able to explain in a brief post, and certainly much more beautiful than any argument I will ever come up with myself. It compresses a vast and turbid system of enmeshed ambitions and behaviors into a deceptively simple nine word thesis.

I recommend the entire piece, which attempts to come to terms with the fact that we’re in a place right now where one of our two parties literally refuses to lose (or have lost) elections, and is steadily eroding the bedrock of our democracy rather than face that possibility in the future. Farrell draws on Brian Eno’s writing about organization and variety to chart a path forward, and it’s pretty compelling3. But I want to linger here on the word “lose.”

It’s an idea that feels counterintuitive, perhaps, but when it’s spun out, as Przeworski does, it makes a great deal of sense. The strength and vitality of democracy doesn’t come from a single leader who (thinks he) knows everything or who’s allowed to stand outside the law. If anything, as we’ve witnessed over the past few months, that kind of narcissism makes democracy much more fragile. And as Farrell explains in a 2023 article, “[The possibility of winning in the future] gives the losers some incentive to accept their loss this time around, in the hope that things will go differently in the future. And that, in turn, helps underpin democratic stability.” But this relies upon an important commitment to the process itself. This is Przeworski: “Democracy is consolidated when … no one can imagine acting outside the democratic institutions, when all the losers want to do is to try again within the same conditions under which they lost.”

The problem, as we’re finding out, is that the inverse of this is also true. The more that our politicians imagine acting outside of democratic institutions (unprincipled rule changes, weaponization, redrawing electoral maps, career politicians, the refusal to separate branches, governing by EO and social media posts, elite and corporate capture, corruption, toxic irony, et al.), the more fragile our democracy becomes4. This dynamic should sound familiar to us, though, as it’s been playing out across society. As Cory Doctorow is fond of noting, across a broad range of contexts, it’s “rules for thee but not for me.”

Przeworski relies on game theory in his analysis, and while we might object that democracy (or government) is not a game, that’s only partly correct. It’s gotten less so over the years, as a function of the size and complexity of the country we ask our government to manage. And it’s gotten less so as our media has focused increasingly on the “horse race” of it all, distancing themselves and the discourse from the real-world impacts both of elections and policy decisions. The career politicians, advisors, and consultants who have monopolized political power certainly think of it this way (as I wrote about a while back)5. As politics has become more and more a game in this country, the folks doing the “winning” spend more of their time hoarding power and money than they do actually deploying those resources on the part of the folks who cast votes for them.

Ironically enough, some of the most notable people across the world, when asked about how they’ve achieved their success, will explain that failure, losing, was a key component of their development. One of the most famous examples of this is Michael Jordan, who failed to make his high school varsity basketball squad his first time out. John Grisham and Stephen King had dozens of rejections before selling their first novels6. Sometimes our failures will motivate us, or cause us to redouble our efforts, learning from the fact that we’ve fallen short. Sometimes they’ll force us to reevaluate, to choose a different path to success that we might not have ever found otherwise. It’s not that it doesn’t suck to lose at something, but it can often be formative.

The small handful of people who are able to insulate themselves from failure, whether through obscene wealth, connections, or power, do themselves no real favors. And that’s to say nothing of the havoc they wreak upon the rest of us, disconnected as they become from the rest of the world and its needs. I think again of Zuck, who’s forcing AI slop onto Facebook7 because he apparently believes that “The average American, I think, has fewer than three friends…” Or the mad king, raging at all of the “losers” who object to his overt violations of the Constitution in accepting gifts from a government as his family conducts billions of dollars of business with them. These guys are too weak to fail, only because they have the resources to surround themselves with incompetents, sycophants, and parasites who’ve attached themselves as a matter of survival. Their entire livelihood depends upon never letting on that these weaklings are anything less than perfect, even as they change their positions, go back on their word, and contradict themselves. We have always been at war with Eurasia, after all. They’re nothing special, outside of the money they have at their disposal to wall themselves off from this truth.

There’s a lot more I could say. I think there’s an important connection between Przeworski’s analysis and the context collapse facilitated by the tech industry, for instance, but I’m going to save that for later. This has already gotten pretty loose, and I wanted to make sure and post it before our next MOST GLORIOUS CELEBRATION OF GREATEST AMERICAN PRESIDENT EVER, so that I could close with one last image. More soon.

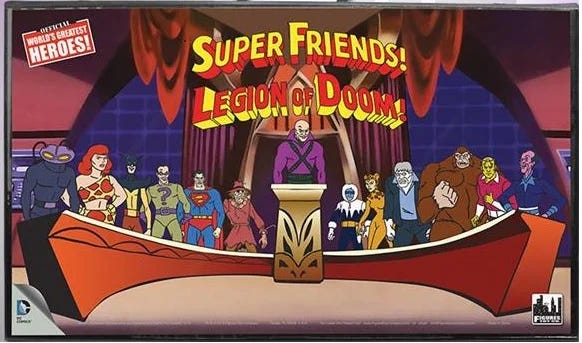

I know that it’s petty and juvenile of me, but I can’t help thinking of that group as the “Legion of Dumb.” As Jennifer Rubin explains, “He actively does not want to hear from people who know what they are talking about, nor does he want to put competent people in his Cabinet lest they contradict his bizarre impulses, hunches, conspiracy theories, and wackadoodle ideas. Forget the ‘best people.’ He needs the worst people, i.e., the sycophantic anti-experts who would never dream of correcting or countering his blather.”

From Rick Reilly’s book on Trump’s “prowess” at golf: “When Trump told Gary Player he’d won 18 championships, Player scoffed. ‘I told him that if anyone beats him, he kicks them out. So, he had to win.’”

The other place in recent years that I’ve come across references to Eno is Dan Davies’ The Unaccountability Machine (about which I wrote a bunch), and if you want to know how an avant garde musician and an old school cybernetics theorist connect, you might start with Farrell’s essay from last fall, “Cybernetics is the science of the polycrisis“

The person who put his hand on a Bible and swore to uphold the Constitution—less than 4 months ago—publicly declared that he didn’t know if had to honor that vow. The bright red line has been crossed, in my opinion.

One of the long lost stories of the 2024 campaign is how Harris managed both to raise $1.5 billion in such a short time, and manage to spend it just as quickly. Say what you will about who “won” and “lost” that election, but I’m relatively sure that the core campaign staff and consultants came out just fine.

Once upon a time, I co-wrote a chapter on the importance of failure for writing pedagogy; writers who don’t have the space to fail and learn from their mistakes end up stunting their growth and hating writing (and/or turning to junk Ai to think for them).

I’m hoping to write more about this pretty soon. Filling up platforms with Ai to make up for all of the people leaving them is the next step in their enshittification.