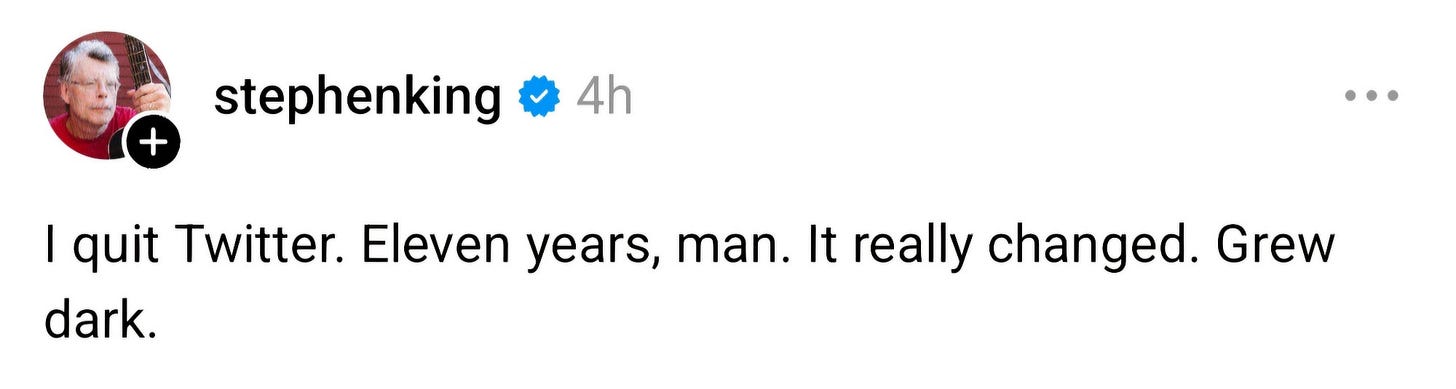

It’s been interesting lately to watch the “quit lit” conversations circulating not only on social media, but about them. I’m thinking about hashtags like #Xit and #Xodus, for instance, which have certainly gathered steam over the past week. If my notifications on Bluesky are any indication, that momentum has been translating into users.

It’s been almost a year since I announced here that I was going to begin the process of withdrawing myself from Twitter, and I’m slightly embarrassed to say that it’s taken me longer than I thought it would. Rather than nuking my account outright, I wanted to work back through my timeline, a process that feels a lot like washing the floor with a toothbrush or digging a grave with a teaspoon. But that’s not to say that it hasn’t had its rewards: there was a time when I was an active conference tweeter, and it’s been fun to revisit ideas from years ago and remind myself how my own thinking has evolved. I’ve worked my way back to 2012 so far, and am currently revisiting the Genre 2012 conference (where I spoke) that summer. In terms of raw numbers, I think I’ve got about maybe 30% of my account left to scrub.

I wrote last year that “each of us must determine for ourself where that line is located, and what we’re willing to do if and when it’s crossed.” For me, it was the cavalier way that Alex Jones was reinstated, although there were plenty of points both before and after that event that gave me pause. The lyrics of the Clash song from which I draw my title include the following:

If I go, there will be trouble

And if I stay, it will be double

That’s the calculus that I (still) believe each of us must engage for ourselves—we have to decide how much trouble we want. The choice to stay or go with any platform involves network effects, the phenomenon by which the value of a media platform increases exponentially as its userbase rises numerically. In the earliest stages of development, network effects are heady and euphoric—every new user is an addition, but the connections they can spawn are multiplicative. At the same time, though, when a platform hits a certain size, it can become an irresistible target for all sorts of grifts, as folks look to tap into and extract viral energy1.

When a platform reaches that stage, though, the network effects that have fueled its growth also lock us in. (that’s part of how enshittification works) The more value we associate with an account on the platform, the harder that platform becomes to leave. All of the connections we’ve made and the community we’ve built there becomes sunk cost. Unfortunately, it also makes us increasingly vulnerable to those who take advantage of a captive userbase.

I’ve been on Bluesky for a little more than a year now, and honestly, I still think of myself as “in transition.” But my experience with Twitter was pretty similar—I was an early adopter, and it took a good while before it felt like an actual platform for me. That’s not to say Bluesky is (or may ever be) Twitter 2.0, although I think its design is grounded in some of the lessons that Twitter taught us. Bluesky offers much more user autonomy and privacy, and a lot of the analytics and monetization options that make Twitter attractive to marketing tryhards are absent. That may mean that the site will never achieve the sort of centrality that Twitter did, but I’m not sure that’s such a bad thing.

It does mean that we will need to move off of the “one platform to rule them all” attitude that has debilitated legacy media and led to a number of the abuses that we’ve experienced over the past 10-15 years. The decentralized infrastructure of Bluesky, more than anything, is intended to help users preserve their accounts and their connections—if the site itself curdles, it would be easier to move elsewhere. In that, for me, it feels like something that overlaps significantly with Twitter, but has some cozyweb baked into it as well. For me, that means that Bluesky will probably won’t ever hold as large a share of my mecology as Twitter once did, but there’s still a place for it.

All that said, I do understand why those who’ve forged community on Twitter might not want to try and rebuild that elsewhere, just as I get why people are attached to their Facebook groups. As precipitously as Twitter’s value has declined over the past couple of years, platforms don’t just collapse overnight (and their value can’t simply be transplanted elsewhere with the wave of a wand). But I’m increasingly optimistic now that Bluesky isn’t invite-only, and more folks seem motivated to find an alternative.

[Update: Rob Horning just posted about Bluesky, saying, among other things, that “Tech writers are now writing their obligatory columns (like this one) about Bluesky, many offering the carefully hedged hope that this time it will be different…” which made me laugh. He also raises an important point later on, that given the shifts in social media, we shouldn’t be longing for Twitter 2.0. We should instead be thinking about how to build a platform that keeps text (vs image and video) as its primary focus. “It almost seems credible that there is a broad constituency for a public sphere that is struggling to be born that is shaped fundamentally by the pleasures of the text and not video.” Here’s hoping.]

Network effects and virality are complementary but distinct, I think I’d argue. The latter relies on the former in ways that aren’t quite reversible. It’s actually more complicated than that, but that’s roughly how I think of them.

Much that once was, is lost. For none now live that remember it...