Nesting

A backwards post about the new puzzle in my life

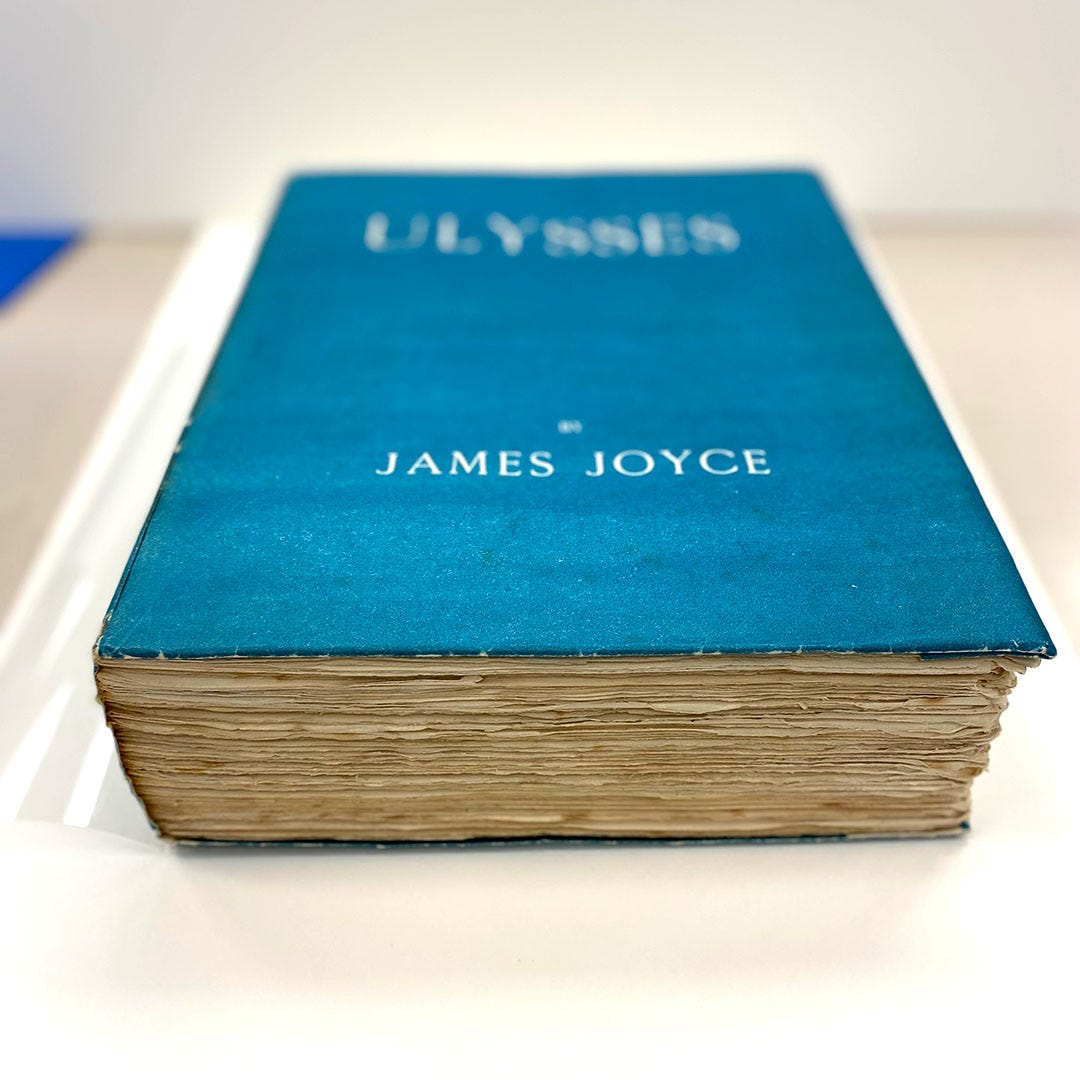

Bloomsday (June 16) is only a couple of weeks away. It’s an international holiday, though mostly focused in Dublin, celebrating the works of James Joyce1, whose novel Ulysses takes place on a single day in that city: June 16, 1904.

One thing that most people wouldn’t know about me is the deep affinity that I felt for Joyce. I spent the final years of my undergraduate degree (in English) fully intending to study Irish literature in graduate school. In part, this was because I spent a term2 (Spring 1989) studying in Dublin.

One of my Dublin courses was devoted entirely to Joyce’s Ulysses; we spent the entire term closely reading and discussing the novel. There are two things that I remember about that course, and one of them’s a brag. We didn’t write a final essay for it, which was unusual enough for a literature course. Instead, the final was a 100-question test about details from the book. For example, in Chapter 6, the funeral procession passes over 4 different rivers, and we were expected to name each in the proper order. (Yes, the questions were almost all that specific.) The bragging part of this is that I scored a 98 on that exam. My memories of it have faded over the intervening 35 years, but I’m not sure that I’ve ever known a book as thoroughly and completely as I knew Ulysses for a time. The second thing that I remember about the course played a role in that, though; the only other assigned “reading” besides the novel itself was a book that’s long since gone out of print (and replaced by more recent offerings). It provided a set of walking tours of Dublin, one for each chapter of the novel. My classmates and I would read a chapter, then head out to encounter all of the physical landmarks that appeared in it. It was an incredible experience in many ways, one that drove home for me that connection between words and worlds that I wrote about last week.

I truly cannot remember whether it was in Dublin or the following year back in Minnesota, but I was so attuned with Joyce3 that I bought my own copy of Richard Ellmann’s classic biography. I devoured it eagerly. I wish I had that copy handy (it’s tucked away in a box somewhere) so that I could quote the passage directly, but one of the details that has stuck with me, for most of my life, is an anecdote about Joyce’s writing process. Joyce was a slow, painstaking writer, famous for the time and effort he poured into the craft, and the intensity of his revision process. At one point, Ellmann talks about how Joyce once spent an entire day writing and revising a single, 8-word sentence, in order to get it to sound right.

It’s not entirely wrong to think of this as craftsmanship and dedication that crosses the line over into obsession. At the same time, though, there was something aspirational for me in this anecdote, the idea that it was possible (and perhaps even beneficial) to care this much about language and its effect upon a reader. It’s something (again) that I kept with me even as I left Joyce and Irish literature behind and shifted my focus over to writing studies. I didn’t want my students to paralyze themselves over a single sentence, especially considering that most of them weren’t (aren’t) likely to spend even one full day on an entire essay. Even so, I wanted them at least to be able to think about language in that way, even if I didn’t expect Joyce-level, S-tier revision.

I’ve tried several solutions over the years, and even shared the Joyce anecdote on a few occasions with students, but this is one of my favorite assignments in this regard. It comes from the Style course that I’ve taught4 several times. One of the exercises that I ask my students to complete is to take a sentence from the scenes that I ask them to write, and to revise it into a sentence that’s at least 100 words long. This is a pretty simple task for anyone who’s spent significant time reading academic prose (for better or worse), but for most of my students, it’s a steep challenge. They’re not allowed to cheat with semicolons or dashes, smushing multiple sentences into one.

A long time ago, I found an online tool that actually made this easier for them. It’s an odd little website called Telescopic Text, and to my delight, it’s still available today. It’s a browser based tool that allows you to take a small sentence and make it clickable and longer, by “folding” in changes.

You can click on words and phrases in the seed text, which are then “unfolded” into their expanded versions (which themselves may be expandable). My account with the site is still active, so if you’d like to see an example, I used it, once upon a time, to contrast four different classic statements about rhetoric.

These expanding sentences provide a light application of sentence diagramming, in the sense that setting up an expanded, complex sentence requires you to think about which elements of a sentence go with each other. Also, you’re beginning with a very simple skeletal core and fleshing it out, which is a different take on a long sentence than most writers will experience on their own.

My favorite in-class assignment using this tool was to take a 100+ word sentence (I vaguely recall that it was from one of John Barth’s novels), and asking students to use the site to reverse engineer it. In other words, they had to figure out how to work that sentence down to its shortest, most essential components, and then use the site’s features to rebuild the sentence. Once you get the hang of it, it’s not an incredibly difficult task (it’s easy enough to fold adjectives and adverbs into the words they modify, for example), but taking a long, complicated sentence and identifying its bones, thinking about clause dependency, etc., encourages you to think about language and sentence construction more explicitly.

I’m pretty sure that this didn’t quite get my students to the point of spending an entire day on a single sentence, but perhaps it made that level of revision intricacy a little more understandable.

Postscript: Bracket City

I have to confess that I wrote this entire post backwards, without any intention whatsoever of talking about Joyce. If I wanted to moralize, I might say that this is exactly the sort of essay that is impossible using AI. But here’s what happened.

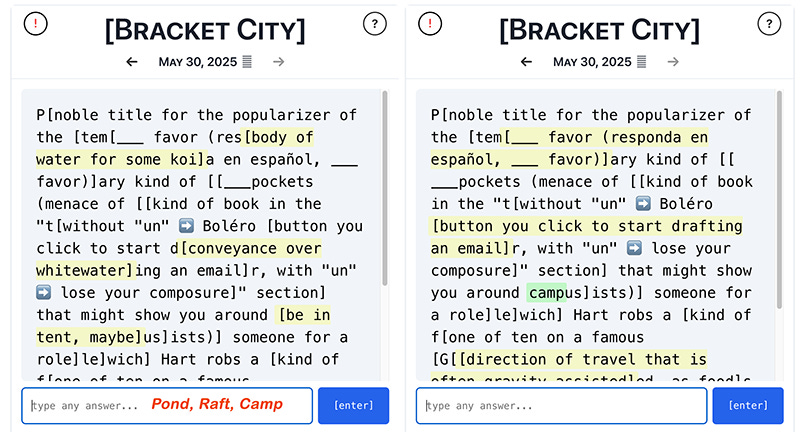

Over the past month or so, I’ve really enjoyed an online puzzle game which was new to me, Bracket City over at The Atlantic’s website. It’s joined Puzzmo and Minute Cryptic as browser tabs that I leave open and just refresh daily. Bracket City takes a news event from that day in history, and then extends it by folding in a whole bunch of nested clues that you have to eliminate by correctly answering them. So in the example below, the left pane is today’s puzzle, while the right pane is what it looks like after I’ve answered the first 3 (yellow highlighted) clues, but before I’ve answered “por” and “compose.”

You can click on each clue twice for help: the first time to get the first letter of the answer, the second time to get the answer auto-filled. But the “puzzle” is kind of a reverse telescope: the answers are often nested within one another, and each correct answer makes the paragraph shorter, until you arrive at the day’s moment in history (Today’s is from 1899: “Pearl Hart robs a stagecoach near Globe, Arizona.”).

As I was thinking about why Bracket City appealed to me so much, it reminded me of TelescopicText. From there, I thought about how I’d used the tool and why, which led me to that anecdote about Joyce, inspiring the reverie about how important Ulysses was to my college-aged, Irish literature-inclined self, and finally to Bloomsday, which is fast approaching (and a potential topic for a “moment in history” puzzle).

Whether you enjoyed this episode or not, it was fun to think about and write for me, and it’s precisely the sort of thinking and writing that artificial intelligence erases from our collective repertoire. We use language just as language uses us, and all that. So it’s not the worst postscript for this recent cluster of posts. More soon.

The protagonist of Ulysses is a man named Leopold Bloom, hence the name.

At Carleton, we were on 10-week trimesters, rather than 15-week semesters.

Another sign of that attunement was that I voluntarily read Finnegans Wake on my own during my senior year. I had to read it in the library, alongside multiple guides to the novel, because it was notoriously complicated and difficult, but read it I did.

I’ve written about that course in some detail, and it only just occurred to me that “glorious chaos” is a pretty accurate term for what Joyce meant to accomplish with Finnegans Wake, even if the effort was largely lost on his readers.

I forgot to add, as a footnote, that the final chapter of Ulysses, Molly Bloom's soliloquy (Penelope), is a 4391-word sentence. There have been writers since who have intentionally exceeded that, but for a long while, I'm fairly certain that Joyce wrote the longest sentence in the English language.

+1 for predicting the June 16, 2025 edition of Bracket City!