As someone who’s both interested in and writes about technology, one of the things that’s always plagued me is the fact that the kind of writing I’m paid to do operates at a much slower pace than the objects of my inquiry. It’s a reason why I was drawn to blogging, and why that sort of writing has always meant more to me than the occasional article or book chapter. While the latter are more permanent (and have always “counted” more), blogging allowed me to pursue lines of thought without the pressure of that final product, without the dance that many technology scholars inevitably find themselves doing to try and bottle the lightning.

My book came out in 2009, but I drafted it in 2004, and perhaps you’ll see the problem when I tell you that Facebook was created in 2004, Reddit in 2005, and Twitter in 2006 (the 1st gen iPhone arrived in 2007). My book took an inordinate amount of time to pass from draft to publication; by the time it arrived into the world, the world itself was, if not substantially different, well on the way to becoming so. When I go back and glance through it, I’m always struck by that difference. I still feel as though the basic structures and ideas of the book are sound—they don’t depend on the relevancy or recency of the examples I use—but the insights feel a little quaint and were already feeling that way to me when I received my author’s copies.

But I do go back to that time, now and again, to remind myself of the vibe of the early 2000s. I did my PhD in the mid 90s, when webpages, hypertexts, MUDs/MOOs and the like were just beginning to tinker with our sense of what was possible. Ten years later, as I was writing my book and social software was on the verge of tipping into social media, there was an optimism about and a vision of the substantial changes that the internet would bring.

One of those visions was the idea of the wisdom of crowds. James Surowiecki’s book with that title came out in 2004, and its message was tailor made for those of us who had really dug into blogging. The idea was that groups could be more than the sum of their parts, accomplishing things that the individuals in the group weren’t capable of. The archetypal example of this is a team of doctors arriving at a diagnosis, but there’s a sense in which democracy itself is based on this notion. There was a palpable sense of democratization at the time: the idea that tagging could democratize categorization and organizational schemes, that blogging would make all of us pseudo-journalists, that book and movie reviews would be revolutionized by sites like Amazon, Metacritic, and Rotten Tomatoes.

And maybe, for a short time, it worked. I don’t know how you’d actually prove or disprove that, but it’s my sense of things that, for a time, most folks approached these sites with something like good faith. The wisdom relies on a few preconditions. It requires decentralization, which the internet certainly provided. It requires (informational) independence of the members of the crowd, which was arguably true of the internet at that point. Finally, the crowd must be fairly diverse, in the sense that it contains as broad a range of perspectives as possible. And yes, this feels like the most arguable to me, although I think that it’s kind of a bracketed diversity, depending on the crowd/milieu being considered. The term itself didn’t carry the same weight almost twenty years ago than it does today.

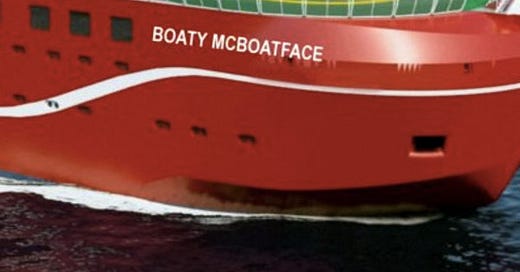

This was a really long prologue to the question that struck me yesterday. I haven’t been Online a great deal lately, so I was unaware that Netflix was releasing its latest chunk of Witcher content (“Blood Origin”) yesterday. I watched the first episode and as I tend to do, I went over to IMDb to check out the names and filmographies of some of the actors. I got there to find that, less than 24 hours after its release, Blood Origin already had 3500 reviews on the site (there are more than 7000 as I write this the next day). And the vast majority of them score the show 1 out of 10, of course. We’ve been sourcing the crowds for years now, and outside of the occasional lulz (Boaty McBoatface!), I’m hard pressed to find a whole lot of wisdom.

The question for me is at what point the potential implied in the wisdom of crowds turned into the vengeance of mobs? It’s interesting to think about, but it’s probably also largely unanswerable. And I think it’s fair to argue that one of the casualties of the shift to social media was the decentralization of the late 90s or early 00s web. You might argue that we saw some of that shift as blogs (and blogging platforms) grew in prominence. And as the Book and Bird (and a shrinking handful of others) centralized our online activity, so too did they effectively wipe out the kind of independence Surowiecki talked about. It was less about independence of thought and more about “private information.” When the boundaries between private and public collapse, and the number of information channels decrease as severely as they have in our media oligopoly, there aren’t any “crowds” left, at least not of the sort that we celebrated in the 00s. And this is to say nothing of an information ecosystem that is bent towards convincing us that there are only two “sides,” incentivizing that choice, then extracting as much as it can from the self-fulfilling prophecy.

The vengeance of mobs is enacted by these isolating, aggressive monocultures on these platforms. Not unlike the goal of “main character” Twitter, I suspect that the trick is to stay under the radar as much as possible. There’s probably a Dunbar number beyond which any rating system gets sucked into, and weaponized by, these polarized culture wars.

This has gotten longer than I’d planned, even though there’s a lot more to say. The last thing I’ll note here is there’s a fracture between what sites like these denote and what they actually accomplish now, and that’s a feature of the current ecosystem. That split, and the way that it emerges across any number of contexts, is one of the things I’ve been thinking on lately.