A couple of weeks ago, when I started that series on scale, I mentioned Kyle Chayka’s book, which was at the top of my to-read pile.

Well, it’s now atop my “finished reading” pile, so I thought I’d write a post or two discussing it. I pre-ordered the book when I first heard about it last fall, so I’d been looking forward to spending some time with it this semester.

I should start by saying that the book wasn’t quite what I had hoped for, given how little time I have right now for reading. I don’t think that this is entirely Chayka’s fault, though. Some of it has to do with the genre, and some of it has to do with unrealistic expectations on my part, honed by a lifetime of working in academia, where standards are different (not necessarily better).

From time to time, I listen to the podcast If Books Could Kill, where the hosts engage in close reads of what they describe as “airport bestsellers,” the kind that you pick up in an airport gift store, read on a flight, and don’t really think too deeply about. I will say that Filterworld is not an airport book, but on a recent episode of the show, the hosts were joking a bit about a recent trend in publishing where someone will post a piece that “goes viral,” then gets invited to turn it into a full-length book.

[More than a year ago, I snarked (as many people did) about Sam Bankman-Fried’s observation that most books would be better as 6-paragraph blog posts. This is sort of the weird (and equally misguided) inverse of that—publishers trying to coattail viral articles into book sales. Also, if those were the kinds of books that SBF was reading, then I feel a little more sympathetic to his position.]

In the case of Filterworld, the viral article in question is a piece that Chayka wrote for The Verge about seven-and-a-half years ago, “Welcome to Airspace: How Silicon Valley helps spread the same sterile aesthetic across the world.” The intention involved in shifting from this title—which is fairly specific, as befits its examples—to the full title for the book (Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture) is probably worth an entire post of its own. In part, we might take it as evidence of how Chayka’s trendspotty essay identified a much broader phenomenon. It might also be evidence of the same kind of upscaling that the IBCK folks discuss. This may come off as a bit mean, but I’m not sure how much better off I am for having read the book than I would have been had I simply read the essay that served as its inspiration.

To an extent, that’s because a great deal of the book feels like it’s collected a bunch of Chayka’s previous work, including “Airspace.” A fair bit of the “evidence” that he marshals for the filterworld thesis comes from personal interviews, which has the effect of feeling anecdotal, a little haphazard, and serves to emphasize the access that he has to people rather than the ideas themselves. (This latter bit is a personal peeve of mine that’s pretty common with this sort of book—the way that long quotes are constantly framed by “X told me” instead of “X explained.” It’s the linguistic version of the cutaway to the interviewer on television.)

Here’s one example. The original “Airspace” argument is an interesting one, but it also echoes a pretty classic book of French cultural theory, Marc Augé’s 1992 Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Super-Modernity. To be fair to Chayka, his original article name-checks Augé, and the encroachment of social media definitely extends Augé’s original (pre-internet) project, which examined the way that spaces like airports, malls, et al. create a “profound alteration of awareness” through their sterility and homogenization. It would also be fair to note that Chayka’s inclusion of Augé in the book is expanded, although really, not as much as it probably should have been. (The bit he does include, which amounts to about a page, comes from Augé’s narrative introduction to the book.)

But I should also mention that this comes in the middle of a section called “Theories of Flatness” that crams together Thomas Friedman, Manuel Castells, Rem Koolhaus, and Gayatri Spivak, along with a digression on Psy’s “Gangnam Style,” all in the space of a few pages. They’re not exactly peas in a pod, which lends an irony to the fact that “theorists of flatness” are here treated themselves with a certain amount of flatness. I don’t expect everyone (or anyone outside of academia) to have read those authors above, but having read one or more books by each of them myself over the years, they deserve better in a book that uses “flat” in its title.

I found it hard not to contrast that section with another from earlier in the book, where a few pages are devoted to a conversation that Chayka had with an engineering graduate student (Valerie Peter) in England who had written in to an advice column in a fashion critic’s email newsletter, about struggling to figure out her own style:

I got in touch with Peter to find out what exactly had caused this crisis of taste, and we ended up discussing how the rise of social media fundamentally changed our relationship to culture.

Yeah, okay, I guess? I do understand that, if you’re writing for a mass audience, you have to find ways to make it personally accessible, and most readers will sooner identify with a young woman’s confusion over the resurgence of leg warmers than they would with a French anthropologist from the 90s. But I did expect better, maybe even a rough balance struck between theory and anecdote (particularly when, later, he treats Koolhaus like a crazy uncle for making “grand pronouncements” that “he doesn’t entirely back up with facts or data.”)

Kevin Munger, whose critique of Chayka’s book is worth reading, explains that “This isn’t a book, in the way we were raised to expect….It’s also not a book on the terms it presents itself, as deeply researched, historically-informed technology criticism.” He cites a couple of other critical reviews, themselves also readworthy, and one of his main points is that this is a book that is so deeply embedded in the flattened culture that it purports to critique that it struggles (and fails?) to see a way out. And that begins with putting all of the responsibility for “flatness” on algorithms (without understanding that “‘The Algorithm’ is today used to disguise the larger systems in which social media are embedded.”). Munger writes, only partly tongue-in-cheek, that “‘The Algorithm’ is the only critique of ‘The Algorithm’ that ‘The Algorithm’ can produce.”

Two more quick points. The first is that I assumed from the title that this book was a critique of the flattening of culture. But I wasn’t convinced until maybe the final chapter or so that Chayka actually felt that way. At a certain point in my reading, I realized that the book’s subtitle, “How Algorithms Flattened Culture,” might just as easily be laudatory. sort of a “Mission Accomplished” banner.

Before the book came out, I listened to Ezra Klein’s podcast interview with Chayka, and he sounds like a smart guy, someone who could have done more with the opportunity that this book represented. Reading it, I was really struck by how the flattening he described was literally part of his own mission, a fact that he acknowledges at one point:

As someone who hangs out online and acts as a sieve for culture-as-content in my career as a journalist, I am a participant and an accelerant of this system. It’s not that I particularly enjoy it or that I want the homogenization to spread further. But most of Filterworld’s inhabitants are either unwilling or unwitting. Simply by trying to make a living or entertain ourselves we accelerate the flattening.

The vibe I got throughout much of it was that he never really gave much thought to the downside of the system he accelerated, so long as he was able to stay in front of it, make a living, and find it entertaining. And a lot of this book recounts the conversations he was having with people while he was still in the process of capitalizing on the trends that he helped identify and propagate. Often, it comes off more as nostalgic than critical.

[I can’t let pass the fact that he equates his journalistic career with “act[ing] as a sieve for culture-as-content.” That’s…something.]

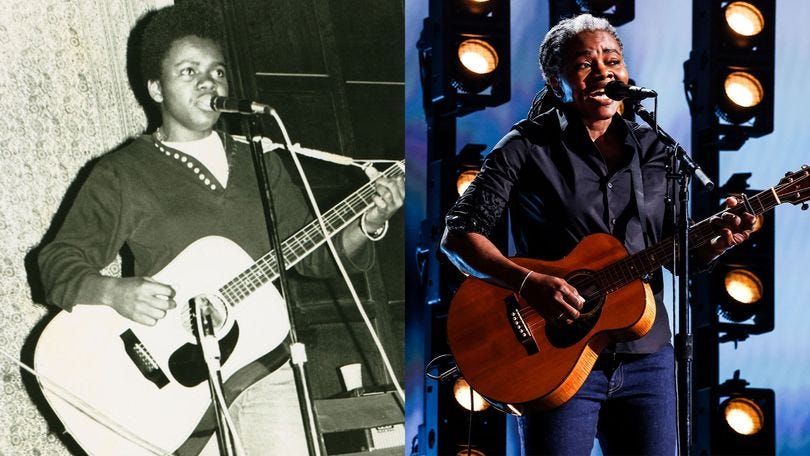

Part of the reason I pulled a line from Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car” for my title here was because I thought it captured this vibe nicely. I understand driving so fast that it becomes intoxicating, but that faux-intoxication doesn’t then excuse what was, initially, a choice. I’m not trying to make the case that Chayka should have been more rueful or apologetic, but a healthy part of his book’s dynamic still relies on the cultural logics that he wants now to resist. And that’s a choice, too.

The other reason for including “Fast Car” here is that, while I was reading Filterworld, I happened across Bomani Jones’ segment on Tracy Chapman’s Grammy performance. The whole thing is ten minutes and worth your time. Jones points out the irony of a room full of millionaires giving a standing ovation to a song about economic desperation. The song is beautiful and timeless, but its message, unfortunately, is also timeless, because in all that time, things haven’t gotten better for most of us. Here’s Sarah Kendzior:

“Fast Car” is not a relic of its time but tragically timeless. Combs’ cover could stay faithful because nothing in this country got better. That “Fast Car” can be passed down through generations without requiring explanation is both a songwriting triumph and a grim indictment of America.

At the very end of his segment, Jones offers a concise, almost poetic account of the “plot” we’ve “lost,” part of which has to do with social media and its algorithms, yes, but there’s more to it:

Look at what brought down the house on that stage.

Look at the people that make the stuff now.

See what the difference is, and you might find out what the problem is.

Filterworld is an insider’s account of that difference, but it doesn’t quite get to the problem, because the way it frames the problem is still coming from the inside. And while some of my disappointment in the book came from its unwillingness to engage its academic sources more seriously, that was just a symptom of a larger problem. I think of it as the “This is water” problem, the degree to which you have to think outside of the thing you want to analyze or critique. Maybe that’s too high a standard, but I don’t think Filterworld quite gets there.

I want to talk about a couple of other ideas that reading Filterworld prompted for me, but I’ll save those for another day. Stay tuned.

Thanks, Collin. I'd written about five paragraphs toward a comment, then got out the little pot still and twenty feet of copper tubing and boiled it all down to this:

Mr. "How Algorithms Flattened Culture" has apparently figured out how to ride this wave; much like the folks in the hall for the Grammys have figured out that riding the wave of our grievances and status anxiety and lost hopes can be monetized, too. Why bother trying to fix the inequity? It's fraught with difficulties, scammers and anger. Nope. We'll all just natter about it. Mission Accomplished. I'll just skip it. But;

While the Machine is tirelessly insidious in its efforts to co-opt (and monetize and corrupt) the light that Chapman and Combs brought to that stage and our ears; Bomani Jones nailed what that moment illuminated (thanks for the link): "Look at what brought down the house on that stage. Look at the people that make the stuff now. See what the difference is, and you might find out what the problem is."

Yet still, despite all the distraction of glitz and glamour and sex appeal and marketing, a little bit of that earnest light shined past and through it all, and as I'd observed before, maybe a few of us remember what it felt like when it eked its way into our truer selves.