I’m in the middle of a post about form, which was prompted by Kornbluh’s book and some other recent reading, but I find myself again this week on the obituary page.

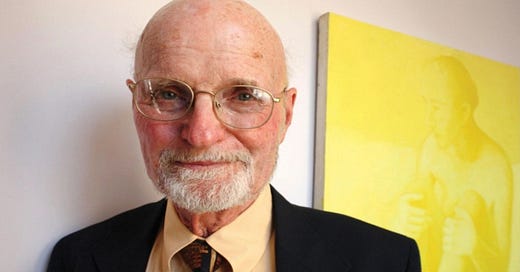

Last week, John Barth passed away. I learned about it from Alan Jacobs, who observed “how odd it must be to outlive your reputation in the way he did, to be famous at thirty and then continue to write for several decades after people stopped noticing.”

While Daniel Kahneman’s work lurks at the heart of the project I’m working on now, Barth was a writer who also has a place on what I like to think of as my “secret syllabus.” I’ve shared this idea in a few places on occasion: rather than think about my favorite book or writer or movie, I like to “answer” questions like those in terms of a longer series of texts that have all had some influence on the way I approach things. In the same way that I might prepare a syllabus, complete with readings and activities, for a course on a particular topic in my field, I think that we (academics, at least) all have a “secret syllabus” that collects the writers, ideas, and styles that have a lasting impact upon us, or perhaps resonance is a better term. As Jorge Luis Borges (another writer on my secret syllabus!) wrote (and Barth quotes approvingly), every writer creates their own precursors.

I’ve never been sufficiently self-engaged to create that reading list in its entirety, but when I come across a name or a book that’s on it, I just know. It’s been decades since I read Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse, for instance, but I still remember the book itself, even if its contents are buried deep in my brainspace. Perhaps the piece of writing that Barth is best known for, though, despite the National Book Award nominations he received for Funhouse and later Chimera, is an essay he penned for The Atlantic in the late 60s, about “The Literature of Exhaustion.” It’s interesting to go back and read that essay, which still felt pretty current to me in the early 90s when I was just starting graduate school. Barth himself was a practitioner of what many described as postmodernist fiction, and his essay was taken to be something of a declaration that a certain (modernist) aesthetic had been “exhausted” of its possibilities. It also goes to some lengths to describe the ways that a writer like Borges managed to do really compelling work in the wake of that exhaustion.

I’m afraid I went into passive voice mode there a bit (“was taken to be” is ugly at best), because Barth would eventually publish a rejoinder to the reception his original essay received. “The Literature of Replenishment” accused many of misreading his “unobjectionable” point that “the forms and modes of art live in human history and are therefore subject to used-upness…in other words, that artistic conventions are liable to be retired, subverted, transcended, transformed, or even deployed against themselves to generate new and lively work.” Unfortunately, he explained, “A great many people…mistook me to mean that literature, at least fiction, is kaput; that it has all been done already; that there is nothing left for contemporary writers but to parody and travesty our great predecessors in our exhausted medium—exactly what some critics deplore as postmodernism.”

[While it’s too far afield for me to treat in depth, I would like to point out that, 50-odd years following Barth’s essay, Kornbluh’s immediatists are responding to the aesthetic that was emerging at the time: “Where postmodernism revels in mediation—intertextuality, irony, the meta—immediacy negates mediation to effect flow and indistinction.” ]

The title story of Lost in the Funhouse provides a fair example of postmodern fiction. The story itself tells of a boy named Ambrose, who “has come to the seashore with his family for the holiday,” but almost immediately, the narrative is interspersed with commentary on the literary devices being employed to tell the story. For example,

Description of physical appearance and mannerisms is one of several standard methods of characterization used by writers of fiction. It is also important to “keep the senses operating”; when a detail from one of the five senses, say visual, is “crossed” with a detail from another, say auditory, the reader’s imagination is oriented to the scene, perhaps unconsciously. This procedure may be compared to the way surveyors and navigators determine their positions by two or more compass bearings, a process known as triangulation. The brown hair on Ambrose’s mother’s forearms gleamed in the sun like. Though right-handed, she took her left arm from the seat-back to press the dashboard cigar lighter for Uncle Karl. When the glass bead in its handle glowed red, the lighter was ready for use. The smell of Uncle Karl’s cigar smoke reminded one of.

The text mirrors itself, doubling, quadrupling, octupling, sometimes dragging itself back to the base narrative, sometimes wandering into infinite regress. There are few points where the story isn’t moving up and down scales, from narration or description, to interpretation and commentary, to authorial reflection, to one or more characters’ internal monologues. Like the funhouse itself, Barth’s story doesn’t allow us to settle in on anything, except maybe unsettledness.

It sends me back to the double movement of literary study (one learns to read, but also to read one’s reading), and to the trope of irony. Barth’s original essay on exhaustion holds up Borges as a writer who’s able to take these (exhausted?) tools and forms and say new things, combining the aesthetic expression of literature with the formal understanding and manipulation required to discover new meanings. Barth begins that essay by commenting on the (for him) gimmicky efforts that “are lively to read about, and make for interesting conversation in fiction-writing classes” but that dispense too quickly with the notion of talent. Borges is his example of “one endowed with uncommon talent, who has moreover developed and disciplined that endowment into virtuosity.” Both writers make use of the distance between connotation and denotation. They’re expert at getting us to read through mirrors, angling our perspective in new and compelling ways. While they’re perhaps not as much to my taste now as they were 30 years ago, Barth and Borges both played a pretty significant role in shaping my own style at one point. And that’s what I set out to say today. More soon.