This is how it works:

Last fall, I wrote about the horrible “just joking” alibi that folks use to excuse their bad behavior. One of the things I linked to was a rant by gaming streamer Negaoryx—in the process of chewing out one of the nits in her chat, she mentioned a bit from a show by comedian Mike Birbaglia, so of course, I rooted around on YouTube to find the segment in question. I thought I had located it, but wasn’t sure. So I discovered that the show in question was on Netflix, and ended up watching the entire thing. Whereupon I learned that Birbaglia’s comedy is less about discrete jokes or even 5-minute bits, and more about combining those smaller units into a much longer, more narrative approach to comedy. And because I’d sought his show out, his other shows started appearing near the top of my recommendations of Netflix (of course), so I watched a couple more. And this week, I was on Peacock, and saw a newly released documentary about his process, and I thought, why not?

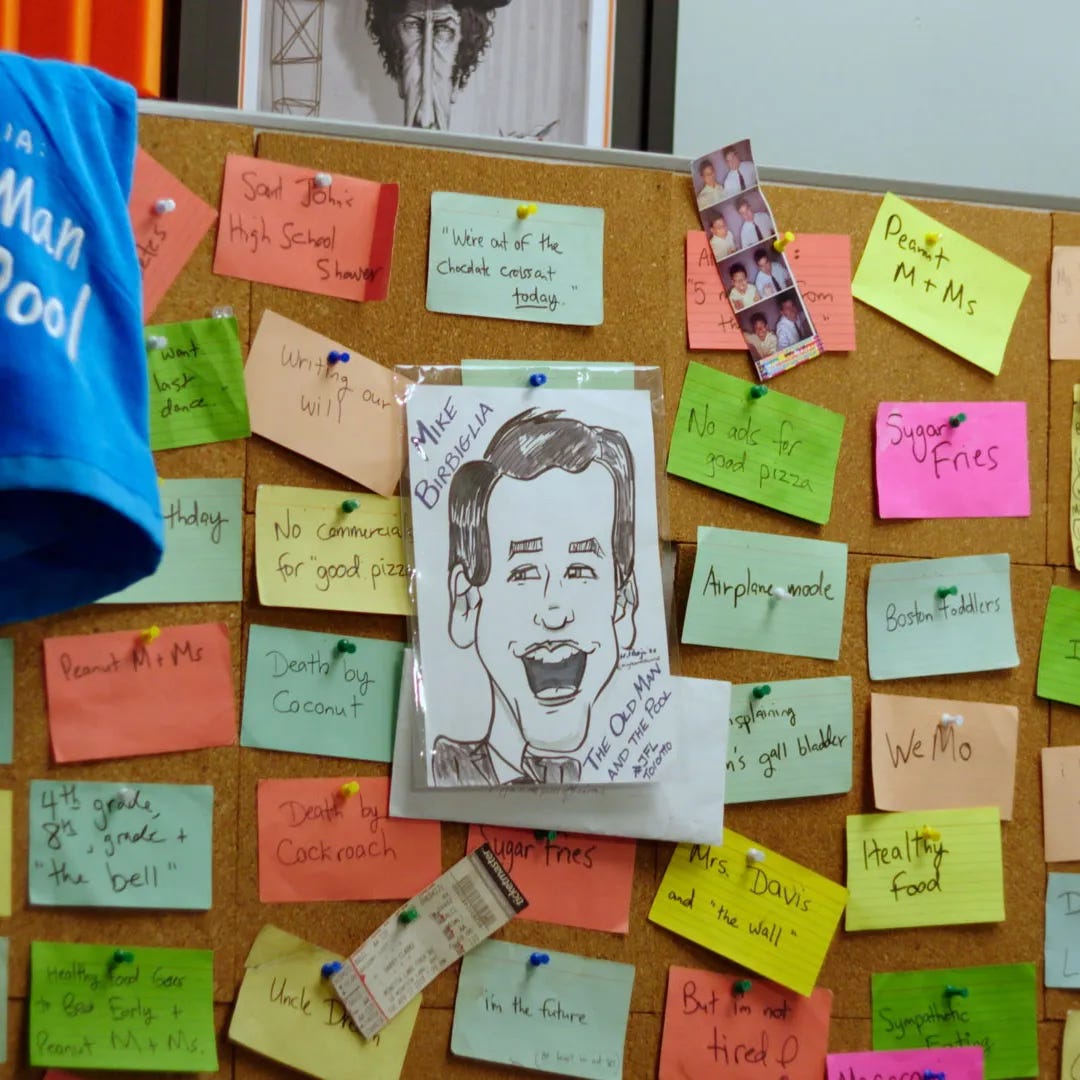

It turns out that the intricate structure of Birbaglia’s shows is (unsurprisingly) the result of a great deal of careful planning, iteration, and a whole lot of note cards.

And that got me thinking, back to an essay that I read a couple of years ago, by Leslie Jamison, where she talked about her own process, which also featured note cards in abundance:

Here’s what Jamison writes about this scene, where she talks about writing an essay about daydreams (as you might gather):

Laid out across the carpet on the second floor of my witch’s cabin (my own treehouse of daydreams), these index cards began to convince me that this infinite map could actually become an essay. Laid out as index cards, the ideas became something I could touch, something I could see, and something I could rearrange. Their delightful physicality helped me understand one of the craft imperatives of the project itself: if I was going to write about daydreams, which were intrinsically, helplessly abstract, I needed to ground the writing in the physical, daily world — all the proximate, ordinary circumstances that daydreams emerge from.

She writes earlier about having arrived at the “the top-heavy black hole of Too Much Research — too many ideas and no idea what to do with them.” She also references a Jorge Luis Borges “story” that imagines a society of cartographers so dedicated that they create “a map of the world that eventually grew as large as the world itself.” (That’s the infinite map she references in the blockquote above.)

There are differences between writing on a site like this and writing to generate a book manuscript—the Borges story that I turn to is “Funes the Memorious.” Ireneo Funes is a young man who, following a head injury, acquires the ability to recall everything he’s ever seen, down to the tiniest detail. While this superpower sounds appealing, particularly to those of us who read for a living, it proves disastrous for Funes, who is only able to “cope” by shutting himself off from the world. And his mental world is like that infinite, one-to-one-scaled map. “To think is to forget a difference, to generalize, to abstract. In the overly replete world of Funes, there were nothing but details.” Blogging, at least as I practice it, doesn’t quite drop down to that scale, but it’s close. I don’t really plan things out ahead of time, and I focus mostly on the texts and ideas I’m encountering in the moment.

(and yes, I’ve been thinking about this lately in part because of Immediacy…)

I wouldn’t describe my own efforts on this site as overly replete, but I’ve grown conscious about how much more challenging it is for (older) me to remember from one month to the next what I’ve written here (even as I use links to set relays and echoes for myself). I feel like, if I want this writing to arrive at a book, I need to do more of the thinking/forgetting that Borges’ narrator describes (or the “mediation” that Kornbluh advocates for). Following Jamison, I think I need to ground my writing in the physical, daily world a bit better, so I think it’s time for me to start working with note cards.

For years now, I’ve made this recommendation to graduate students working on their dissertations. One of the real challenges of graduate school in general (and part of the reason that I’m generally leery of our emphasis on seminar papers) is learning how to make the transition from writing tasks that can be dispatched quickly to projects that need to be managed over the long term. That skill, project management, receives so little emphasis in graduate school, and yet, it’s relevant to a whole host of academic practices, from writing books to planning courses to designing curricula. The ability to scale up and down from individual paragraphs to sections to chapters to books themselves is, nine times out of ten, the decisive element in determining whether or not someone will finish a doctoral degree. As someone who brute forced it for my own dissertation, I’d say that it’s not impossible to do without those skills, but it makes success much more unlikely.

There are certainly other tools that I could use (and have before), but I think I’m going to give note cards a try. I don’t think it’ll have much impact on what and how I write here, but I’m hoping that the extra layer of scale will get me moving a bit more steadily towards my long term goal for this work. With summer approaching, I suspect that it will be a good time to experiment. I’ll let you know how it goes.