About a year and a half ago, I posted something like this as a Twitter thread—it got a little bit of engagement, but by then, I’d already basically been D-listed by the site, so I don’t think most people saw it. And I wanted to save it, so here we are.

Last week, I reposted my hit piece on seminar papers, which makes it a good time to venture to the other extreme. This may be my single favorite assignment of all time. I developed it for an independent study, so it would probably be more accurate to say that we (my student and I) developed it. At the time, I was part of a group that was getting into tabletop gaming, and I was reading a lot of game studies scholarship. I never quite incorporated that area into my own scholarship, although I still keep an eye on it to this day. But that will give you some context for this assignment, which is pretty simple:

Choose a Cornell box.

Imagine that, as you were rummaging around in a basement or attic, you found this box, and recognized it as a game that you used to play, only now it's missing pieces, instructions, etc.

Your assignment is to write the instructions/rules for the game that the (incomplete) box represents. You can add stuff in, but you have to account for everything that's already there. In other words, reverse engineer the game for which your Cornell box is the kit.

Easy, right?

“Cornell box” refers to the art of Joseph Cornell—there are a number of collections of his work available online, but this one from the Smithsonian has a nice gallery (and the link below to Solar Set shows off some others as well). As the liner notes for a Royal Academy of Arts exhibition of his work explained,

Cornell hardly ventured beyond New York State, yet the notion of travel was central to his art. His imaginary voyages began as he searched Manhattan’s antique bookshops and dime stores, collecting a vast archive of paper ephemera and small objects to make his signature glass-fronted ‘shadow boxes’.

These miniature masterpieces transform everyday objects into spellbinding treasures. Together they reveal his fascination with subjects from astronomy and cinema to literature and ornithology and especially his love of European culture, from the Romantic ballet to Renaissance Italy.

I’ve always found Cornell boxes deeply appealing, and I have several containers around my house that function similarly—they’re full of things that I can’t quite bring myself to part with, and they summon up all sorts of memories of different times in my life, places I’ve lived, concerts and shows I’ve seen, etc. Maybe it’s the hoarder in me, but the last thing I want to do with a “junk drawer” is to declutter it—for me, there’s a kaleidoscopic beauty in them.

Anyway, I also grew up with all sorts of board games, and I remember how those boxes would wear out. So sometimes, we’d have to use one box to hold all the bits and bobs from other games, and then those boxes would wear out, too, and you’d end up with a mix of boards and pieces from multiple games. The idea that there might be some larger game that included all of them always piqued my curiosity (and might explain my fondness both for Plan B’s Century series and Hesse’s Magister Ludi).

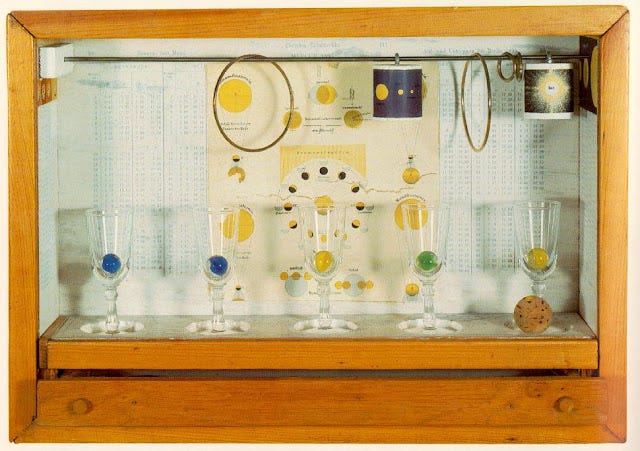

That’s a little bit of the personal background for the assignment. Here’s the box that my student (Jana) chose:

and the game that she designed was called Mission: Perilous Planet. It was amazing, and I can’t tell you how much fun it was to “assess” this assignment by playing it.

As an added bonus: part of the reason that I posted on Twitter about this assignment when I did was because I learned at that time of the work of Karla Knight. If I remember correctly, someone I follow had linked to this piece of hers, Blue Navigator 2. I thought to myself how it could be the board for an alien game, and that in turn prompted my return to Perilous Planet.

I’ve designed a lot of assignments (and a lot of different assignments) over the years, but my Cornell Game assignment is my all-time favorite. Part of me still holds out hope that I’ll be able to use it again, but we’ll see.